Enshrined in 1855: Bordeaux’s Classification and Its Enduring Legacy

A critical exploration of Bordeaux’s 1855 wine classification – its imperial origins, long-term impact, rare revisions, and the enduring debate over its relevance.

Introduction

In the annals of fine wine, few events loom as large as the Bordeaux classification of 1855. In a single stroke, this 19th-century ranking codified a hierarchy of wineries that would come to dominate perceptions of quality and prestige in Bordeaux for generations. Issued as part of an imperial exhibition, the classification was never intended to ossify into permanent canon – yet nearly two centuries later it remains largely intact. Its influence on Bordeaux’s wine trade, culture, and global reputation has been profound. At the same time, the classification’s immutability has sparked perennial debate: How can a static list from 1855 continue to reflect the realities of fine wine in the 21st century? This article examines the origins and context of the 1855 classification, its historical significance and longevity, the few adjustments made over time, and the continuing controversies over whether (and how) such a hierarchy should be revised. The goal is a deep, long-term perspective – analyzing not only what happened in 1855, but why it still matters today.

Imperial Origins of a Wine Hierarchy

The 1855 classification was born at the intersection of imperial ambition and local expertise. In the spring of 1855, France was preparing for the Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair) in Paris. Emperor Napoléon III, eager to showcase the nation’s finest products, requested each major wine region to submit a ranking of its best wines. In Bordeaux, the task fell to the city’s Chamber of Commerce and the Syndicat des Courtiers (wine brokers’ syndicate), who had long been the intermediaries in the wine trade. These brokers possessed intimate knowledge of the region’s châteaux and market prices, making them well suited to compile a “classification of excellence.”

From the outset, the brokers approached the assignment pragmatically rather than romantically. They did not convene a grand tasting or attempt a sensory evaluation of decades of vintages. Instead, they relied on a more empirical metric that the marketplace had already established: price. Over the preceding decades (indeed, even stretching back to the 18th century), certain Bordeaux châteaux had consistently commanded higher prices than others, reflecting a reputation for quality and desirability. As one broker involved reportedly cautioned, “this classification is a delicate task and bound to raise questions; remember that we have not tried to create an official ranking, but only to offer you a sketch drawn from the very best sources.” In essence, the 1855 list was an official ratification of an unofficial hierarchy that wine merchants and connoisseurs already recognized.

It’s important to note that by 1855, Bordeaux’s top wines were hardly a secret. Britain and other export markets had been avid consumers of Bordeaux (“claret”) for generations, and informal rankings had emerged long before. The famous statesman and oenophile Thomas Jefferson, after visiting Bordeaux in 1787, recorded his own list of the region’s best growths – with Château Lafite, Latour, Margaux, and Haut-Brion at the top. These same four estates were ultimately crowned as the highest tier in 1855. In a sense, the brokers simply put a formal stamp on a qualitative hierarchy that had evolved through decades of trade. What made the classification “official” was its inclusion in the Bordeaux region’s submission to Napoléon III’s exhibition – a prestigious catalog intended to educate and impress an international audience.

Scope and Criteria of the 1855 Classification

Crucial to understanding the 1855 classification is recognizing its limited scope. Despite the broad title “Classification of Bordeaux,” the list was confined almost entirely to the wines of the Médoc on Bordeaux’s left bank, along with the sweet wines of Sauternes and Barsac. Only a single estate from outside these areas made the cut: Château Haut-Brion from Graves (just south of the city of Bordeaux), included among the top reds thanks to its longstanding renown. Entire swathes of Bordeaux – most notably the right bank appellations of Saint-Émilion and Pomerol – were absent. This exclusion was not due to a judgment that those areas lacked quality, but rather a reflection of 19th-century trade realities. The brokers were tasked with ranking the wines under the purview of the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce; the right bank fell under a separate jurisdiction (the Libourne Chamber of Commerce) and was not consulted. Moreover, in the mid-1800s the right bank’s wines had less exposure in export markets and a more local reputation. As a result, stalwarts like Château Ausone or the now-mythic Château Pétrus did not appear in 1855 – simply because they were not part of the brief. The classification’s focus was sharply on the left bank grands vins that dominated commerce at the time.

The ranking itself was divided into five tiers for red wines, which the French termed crus (growths). At the summit were the Premiers Crus (First Growths), followed by Deuxièmes Crus (Second Growths), and so forth down to Cinquièmes Crus (Fifth Growths). In total, the red wine list initially comprised some 60 châteaux – all from the Médoc except Haut-Brion. For the sweet white wines of Sauternes-Barsac, a separate three-tier ranking was established: at the top a unique Premier Cru Supérieur (a distinction awarded solely to Château d’Yquem), then a group of Premiers Crus, and a second tier of Deuxièmes Crus. The decision to highlight sweet wines in this way acknowledges that, although red claret reigned supreme in market importance, the unctuous botrytised wines of Sauternes had their own esteemed following in the 19th century.

By what criteria were the châteaux ranked? The brokers explicitly based their decisions on each estate’s historical reputation and, above all, the prices its wines fetched on the market. Surviving records indicate approximate price bands that corresponded to each tier. For example, the handful of First Growths had been selling for around 3,000 francs per barrel, whereas Fifth Growths were in the 1,400–1,600 franc range. Broadly speaking, price was taken as a proxy for quality – a reasonable assumption in an era when pricing information was one of the few objective measures available and when the most respected wines did indeed command the highest prices. It was understood even then that a château’s reputation could rise or fall over decades, but the 1855 snapshot aimed to reflect the pecking order as it stood at that moment, based on roughly forty years of market data (from the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 up to 1855). This method, while empirical, was not without controversy: lesser-known producers who felt overlooked had little recourse, and no formal re-evaluation was planned. Indeed, the brokers themselves seemed aware of the sensitivity of codifying a hierarchy. Their 18 April 1855 report strikes a cautious tone, implying that the classification was a practical guide for the exposition rather than an eternal decree.

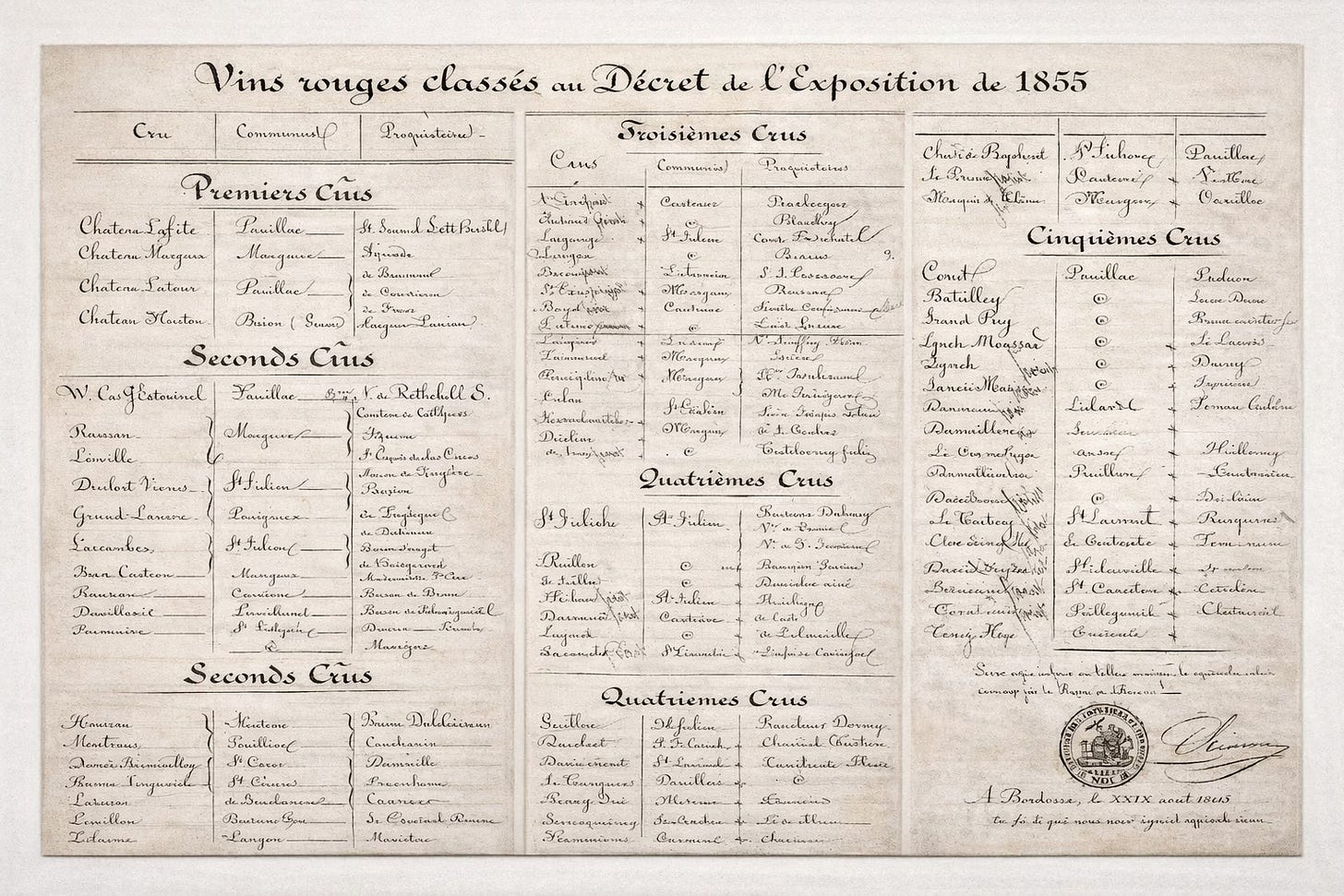

The Classified Growths of 1855

When the results were finalized, the 1855 classification for red wines comprised five ascending ranks:

Premier Cru (First Growth) – 4 estates initially: Château Lafite, Château Latour, Château Margaux, and Château Haut-Brion. These were the most celebrated Bordeaux châteaux of the day, each with a towering reputation. (Château Haut-Brion’s inclusion, despite being in Graves not the Médoc, underscores its status even then as a wine of international acclaim.)

Deuxième Cru (Second Growth) – 14 estates, including illustrious names like Château Mouton-Rothschild, Château Rauzan-Ségla, Château Léoville (Las Cases, Barton, and Poyferré), Château Durfort-Vivens, Château Gruaud-Larose, Château Cos d’Estournel, and others. These were extremely well-regarded properties a notch below the first tier. Notably, the list placed Château Mouton-Rothschild at the top of the Second Growths, a detail that would later take on great significance. (More on Mouton’s story in a moment.)

Troisième Cru (Third Growth) – 14 estates, among them Château Kirwan, Château Palmer, Château Giscours, Château Calon-Ségur, Château d’Issan, and others spread across Margaux, Saint-Julien, and Saint-Estèphe. Some Third Growths were sizable properties producing excellent wine, though perhaps without the consistent record of high prices that the Seconds enjoyed.

Quatrième Cru (Fourth Growth) – 10 estates, including Château Saint-Pierre, Château Talbot, Château Branaire-Ducru, Château Duhart-Milon, Château Beychevelle, Château Prieuré-Lichine, and a few more. By the fourth tier, many names were (and remain) still very respected, though the group’s average prices in the early 1850s were lower than those of the tiers above.

Cinquième Cru (Fifth Growth) – 18 estates, the largest group. Among them were Château Pontet-Canet, Château Grand-Puy-Lacoste, Château Lynch-Bages, Château Dauzac, Château d’Armailhac (then called Mouton-Baronne-Philippe), Château Haut-Bages Libéral, Château Batailley, Château Haut-Batailley, Château Léoville-Poyferré(actually a Second Growth but often listed among Fifths due to an historical mix-up in early documents), and Château Cantemerle (more on Cantemerle shortly), along with others. Fifth Growths in general were solid Médoc properties that made the cut as among the best, but at the lower end of the price/reputation spectrum in 1855.

For the sweet white wines, the classification was shorter but equally strict:

Premier Cru Supérieur – only Château d’Yquem. Yquem’s singular status reflected its 19th-century reputation as the pinnacle of Sauternes, commanding prices above all others in its category.

Premier Cru (First Growth sweet wines) – 11 estates, including famed Sauternes such as Château La Tour Blanche, Château Coutet, Château Guiraud, Château Rieussec, and others in Sauternes and Barsac.

Deuxième Cru (Second Growth sweet wines) – 15 estates, among them Château Doisy-Daëne, Château Suau, Château Broustet, etc., representing the next tier of quality in luscious sweet wines.

The publication of this classification caused a stir, but not a shock. Contemporary accounts suggest that the list was greeted as mostly a confirmation of what the trade already believed. The English wine market, in particular, had effectively “ranked” Bordeaux châteaux through pricing for years. The 1855 ranking solidified the terminology – after this, one could speak of a “Second Growth” or “Fifth Growth” wine and be understood. Initially, the list of châteaux within each class was presented in order of their perceived rank or price within that class. This led to some immediate grumbling. For example, Château Mouton-Rothschild appearing at the head of the Second Growths implied it was the “best of the rest” – a consolation that evidently did not satisfy its owner, Baron Nathaniel de Rothschild. To avoid bruised egos and internecine disputes, the classification was soon reprinted with each tier’s châteaux listed alphabetically rather than by rank order. Thus, within a given growth (say, the Third Growths), no official distinction was made between the first-listed and the last-listed property. Nonetheless, everyone knew which names carried the most cachet in each category. Mouton-Rothschild, for instance, was widely acknowledged as nearly first-growth in stature despite technically sitting in the second tier.

One must also bear in mind that in 1855 the concept of selling wine by château label to consumers was still developing. Much Bordeaux wine was sold in barrel to négociant merchants who often blended or re-labeled it for sale in various markets. The classification therefore initially served industry insiders – a guide for courtiers, merchants, and export agents about whose barrels deserved the highest prices. Only later, as château bottling became standard and labels proudly sported “Grand Cru Classé en 1855,” would the classification attain the direct consumer-facing prestige it has today.

An Hierarchy Frozen in Time

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the 1855 classification is how little it has changed. What was intended as a snapshot of market opinion in the mid-19th century became ossified as a quasi-permanent ranking. Through phylloxera blights, economic depressions, world wars, and countless shifts in viticulture and ownership, the 1855 classed growths held their ranks. This endurance was not by grand design but by inertia – once the list was canonized, no mechanism for regular updates existed. Unlike some other regions (or even later Bordeaux classifications) that planned periodic revisions, the 1855 hierarchy simply persisted by default.

That is not to say nothing changed on the ground. Over time, many châteaux underwent significant transformations. Vineyard boundaries in Bordeaux are fluid: classified estates acquired or traded plots of land, sometimes expanding their acreage considerably beyond what it was in 1855. Other estates might have lost parcels or been subdivided among heirs. Yet no reclassification ever accompanied these agricultural and commercial changes. A château that doubled its vineyard area by buying neighboring land could still produce “Grand Cru Classé 1855” wine from the new plots – even if those plots were never considered top-tier in the 19th century. The classification, being tied to the name of the estate and not a delineated piece of terroir, allowed for such evolution. In a few cases, single estates listed in 1855 later split into multiple properties, each of which then carried the same official class. For example, the large Second Growth estate Château Léoville in Saint-Julien was later divided into three separate châteaux (Léoville-Las Cases, Léoville-Barton, and Léoville-Poyferré); all three still claim the Second Growth title today by virtue of their shared origin. Similar situations occurred with Château Pichon-Longueville (split into Pichon Baron and Pichon Comtesse de Lalande, both continuing as Seconds) and Château Batailley (split into Batailley and Haut-Batailley, both considered Fifth Growths). Thus, the number of classified estates slowly expanded from the original list as some lineage splits occurred. Conversely, one estate on the original list disappeared: Château Dubignon, a Third Growth in Margaux, was absorbed into a neighbor (Château Malescot St. Exupéry) by the late 19th century and ceased to exist as an independent label.

Quality, of course, did not remain static across these estates. In some eras, certain classed growths fell into decline due to poor management, economic hardship, or viticultural calamities. The classification, however, had no provision to demote a château for underperformance. A striking example often cited is Château Margaux – a First Growth whose wines in the 1960s and early 1970s were widely regarded as well below the estate’s illustrious potential. Yet Margaux retained its top classification through its doldrums, and investors eventually rejuvenated it in the 1980s to once again produce wines worthy of Premier Cru status. Similarly, on the lower rungs, a Fifth Growth like Château Lynch-Bages (in Pauillac) steadily improved over the 20th century, to the point that many critics now consider it of Second Growth quality (some dub such cases “super seconds” even though officially they remain Fifths). But Lynch-Bages is still, on paper, a Cinquième Cru Classé – proof that the 1855 titles don’t always synchronize with current performance.

In short, the 1855 ranking froze a dynamic reality into a rigid hierarchy. It bestowed a powerful marketing halo on the classified châteaux – one that they have zealously guarded ever since. Being a “Grand Cru Classé de 1855” has proven enormously advantageous in terms of prestige and price. By the same token, those left outside the classification had to work much harder over the decades to gain recognition. It is no accident that in modern times virtually all the most expensive and sought-after red wines of the Médoc are produced by classed growths. The classification created a kind of aristocracy of wine estates – a status that conferred not only bragging rights, but often easier access to capital, higher land values, and the incentive to invest in quality to live up to the name. Bordeaux, ever a commercially savvy region, saw its grand châteaux lean into the classified growth system as a cornerstone of branding. Even today, a château proudly printing “Grand Cru Classé en 1855” on its label invokes a lineage that few wine regions in the world can match.

Rare Revisions and Notable Changes

For a list so static, it is noteworthy that only two formal changes have been made to the 1855 classification since its inception – and both are often described as exceptions that prove the rule. The first change came almost immediately: in 1856, Château Cantemerle was added as a Fifth Growth. Cantemerle, a respected Haut-Médoc estate, had been mistakenly omitted from the original roster (some accounts say its inclusion arrived too late to meet the exposition printing deadline). After lodging a complaint with evidence of its rightful place, the estate was inserted into the classification the following year. This early episode made clear that the classification was considered official enough that an estate would fight for entry – even at the lowest rank – rather than remain unclassified.

The second, far more dramatic change came over a century later. In June 1973, Château Mouton Rothschild was elevated from Second Growth to First Growth status. This was an unprecedented promotion, breaking the long-held taboo against altering the 1855 order. It happened only after decades of persistent lobbying by Mouton’s owner, the late Baron Philippe de Rothschild. Baron Philippe (whose family had owned Mouton since 1853) waged a tireless campaign throughout the mid-20th century to rectify what he and many others saw as an historical oversight. Mouton Rothschild, with its long pedigree and outstanding terroir in Pauillac adjacent to Château Lafite, was widely regarded by the mid-1900s as equal in quality to the original First Growths. That it remained officially a Second Growth was an affront to both the estate’s pride and (presumably) its pricing potential. Baron Philippe famously adopted the slogan “Premier ne puis, second ne daigne, Mouton suis” – roughly, “First I cannot be, Second I do not deign to be, I am Mouton” – emblazoning it on posters and even the château’s wall, signaling his dissatisfaction with Mouton’s lot. After years of behind-the-scenes pressure and formal petitions, the French agricultural authorities (reportedly with the young Minister of Agriculture Jacques Chirac’s signature) agreed to a one-time reclassification. Thus, in 1973 Mouton Rothschild officially joined Lafite, Latour, Margaux, and Haut-Brion in the charmed circle of Premier Cru Classé. The triumph was sweet: Mouton promptly changed its motto to “Premier je suis, Second je fus, Mouton ne change” (“First I am, Second I was, Mouton does not change”), and the 1973 vintage label was designed by artist Pablo Picasso in celebration. Importantly, this upgrade remains unique – no other estate has ever been promoted or demoted in the 1855 list aside from Cantemerle’s initial addendum. Mouton’s elevation is often cited as proof that change is possible, but only under truly exceptional circumstances and influential advocacy.

Apart from those two officially sanctioned revisions, no others have occurred. A few technical adjustments can be noted: as mentioned, one Third Growth (Dubignon) was merged out of existence in the late 19th century, reducing the count by one. A handful of estates have undergone name changes or splits, but they retained their classified status under the new names (for example, Château Pouget in Margaux was long marketed under the name Château Pouget-Lassale in the 20th century, yet its Fourth Growth rank never changed). Also, between 1855 and today, the practice of using “Château” in estate names became standard; in 1855 only a minority of the listed properties were officially styled “Château X,” whereas now virtually all Bordeaux estates use the prefix. This is a superficial change in nomenclature reflecting evolving marketing, but it underscores how the presentation of classed growths has modernized even as the composition of the list remains rooted in history.

Controversies and Calls for Reclassification

By the mid-20th century, as the fine wine market expanded and quality improved across Bordeaux, many observers began to question whether the 1855 classification still reflected reality. The notion that a ranking frozen in 1855 could perfectly mirror the quality hierarchy of the 1950s or 1980s (or 2020s) was inherently dubious. New challengers had emerged – unclassified estates making superb wines, and classed growths that had greatly improved or declined. This led to repeated calls for a re-examination of the classification. Yet in Bordeaux, such calls ran up against powerful entrenched interests. The proprietors of classed growth châteaux had every reason to oppose any attempt at reclassification that might threaten their status. Conversely, estates outside the classification (or stuck in a lower tier) had everything to gain from a shake-up. The stage was set for controversy.

One major attempt at reclassification took place around 1960. The Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce, prodded by discontent in the ranks, convened a committee (which included notable figures like wine writer Alexis Lichine) to study possible revisions. This committee recognized many anomalies. They noted that some Fifth Growths and even non-classified estates were producing wines on par with Second Growths, and that the strict left-bank focus ignored high-quality areas like Graves, Saint-Émilion, and Pomerol. The committee proposed a bold overhaul: a new classification with only three tiers, some 13 châteaux added that were omitted in 1855, and about 18 under-performing châteaux removed or downgraded. Crucially, they envisioned periodic updates (perhaps every five years) to keep the classification current.

However, as soon as details of this proposal leaked, the backlash was ferocious. Chateau owners slated for demotion or deletion were outraged; lawsuits and recriminations brewed before any changes could be agreed. Ultimately, the revision attempt collapsed under the weight of opposition. The Institut National des Appellations d’Origine (INAO), which oversees French wine classifications, was asked to intervene but demurred, seeing the political and economic stakes as beyond its remit. After two years of fruitless debate, the effort was quietly abandoned. Alexis Lichine, convinced of the need for change, took matters into his own hands by publishing an unofficial “alternative” classification of Bordeaux in 1962 (with updates in subsequent years). Lichine’s personal classification scrapped the numeric growth system in favor of categories like “Outstanding Growths” and “Great Growths,” and it included top estates from Graves, Saint-Émilion, and Pomerol alongside the Médoc. He also elevated some overachieving Fifth Growths upwards. Yet for all his advocacy and multiple editions of Lichine’s classification, the official 1855 list remained immovable. Lichine famously spent over 30 years campaigning to reform the system, only to see little change except the one promotion of Mouton Rothschild, which he applauded. In a later reflection, he noted that attempts to update classifications invariably meet resistance – pointing to the example of Saint-Émilion’s modern reclassifications, which had ignited legal battles among châteaux whenever downgrades occurred. By the 1980s, Lichine conceded that no comprehensive reclassification of the Médoc was likely to succeed given the fierce self-interest at play.

Other critics and writers have made their own assessments over time. The American wine critic Robert M. Parker Jr. published a list of the top 100 Bordeaux estates in 1985, essentially a personal ranking that mixed right bank and left bank and paid no heed to 1855’s verdict. British wine authorities like Clive Coates, MW and David Peppercorn, MW have also offered revised classifications in books or articles. These efforts, while illuminating, have remained informal exercises. No official body has dared to systematically re-grade the classed growths for fear of the economic upheaval it would cause. The reality is that a downgrade could be financially ruinous for a château’s brand, while an upgrade for a few would cast a shadow on those left behind. Thus, the status quo prevails – not necessarily because everyone believes the 1855 list is perfect, but because it has become too politically and commercially sensitive to alter. The phrase often heard is “they mostly got it right in 1855.” Whether or not one agrees, this sentiment provides cover to avoid reopening Pandora’s box.

Modern Perspectives: Relevance and Limitations

What does the 1855 classification mean in today’s Bordeaux? On one hand, it is still a badge of honor and a crucial marker of prestige. The top tier properties – now five First Growths since Mouton’s ascension – continue to occupy the summit of pricing and collectability in Bordeaux’s left bank. The market heavily uses the classification as shorthand: in trade exchanges and auctions, wines are often grouped or compared by their 1855 rank. A collector or sommelier will immediately understand the implication of a “Second Growth from Saint-Julien” or a “Fifth Growth Pauillac.” The language of First through Fifth Growths is deeply ingrained, not just historically but in the current commercial arena. Many of the classed growths themselves emphasize their status in marketing, and the governing bodies of Bordeaux (such as the Conseil des Grands Crus Classés 1855) actively promote the legacy and excellence of these estates as a group.

However, the limitations of the classification are ever more apparent in the 21st century. Quality in Bordeaux has risen across the board due to modern viticulture, global investment, and a generation of ambitious winemakers. Some crus classés that were middling performers in the past are now making superb wines that far outshine their old reputations. Simultaneously, a number of estates outside the 1855 ranking have achieved heights of quality and renown that place them firmly in Bordeaux’s elite. The most glaring examples are on the right bank: châteaux like Pétrus, Le Pin, Cheval Blanc, Ausone and others from Pomerol and Saint-Émilion fetch prices equal to or exceeding the First Growths, yet they remain “unclassified” in the 1855 sense (Saint-Émilion has its own separate classification system, but that’s another story). Even within the left bank, there are prominent names omitted in 1855 because they were lesser-known then or geographically outside the Médoc. For instance, Château La Mission Haut-Brion in Pessac-Léognan (across the road from Haut-Brion) is today regarded as one of Bordeaux’s greatest red wines – some would argue it is effectively a “sixth First Growth.” But La Mission Haut-Brion, not being part of the Médoc list in 1855, is not a Grand Cru Classé by that ancient standard. It underscores the fact that the 1855 classification was never comprehensive: it was a snapshot of a select zone, now fossilized.

The static nature of the classification has led many to conduct thought experiments: What if we reclassified Bordeaux today? Some have attempted to do just that using modern data. For example, the London-based wine exchange Liv-ex periodically publishes a “recalculation” of the 1855 classification based on current global market prices for recent vintages. These modern re-rankings are revealing. In one such analysis, several right bank icons (Pétrus, Ausone, Cheval Blanc, etc.) would unequivocally be First Growths if price were the guide, and a number of left bank estates that were unheralded in 1855 (such as Château Pontet-Canet, a Fifth Growth that has risen to stardom in recent decades, or Smith Haut Lafitte in Pessac-Léognan) would graduate to higher tiers. Conversely, a few venerable names might slip down a rank or two if judged by contemporary price or critical consensus. Such speculative reclassifications are interesting academic exercises – they demonstrate that while the 1855 hierarchy still broadly correlates with quality and price, there are plenty of individual deviations. Crucially, none of these modern lists have any official standing. They serve to spark debate (and sometimes bruised feelings), but the 1855 classification itself remains untouched and is likely to remain so.

Bordeaux does have other classification systems that operate with periodic revisions. The most notable is the Saint-Émilion classification, first established in 1955 (perhaps not coincidentally a century after the Médoc’s) and designed to be updated roughly every ten years. Indeed, Saint-Émilion’s ranking was revised in 1969, 1986, 1996, 2006, 2012, and 2022 – but not without turmoil. Each revision has brought lawsuits from châteaux unhappy with their new status, and in 2006 the entire classification was temporarily annulled by a court ruling before being reinstated. The Saint-Émilion experience shows that dynamic classifications carry their own challenges: they strive to reflect current quality, but constant change can breed discord and instability. In Graves (Pessac-Léognan), a classification of top estates was made in 1953 and slightly expanded in 1959, and that list also remains largely static (though it covers both red and dry white wines in that region). Meanwhile, the Médoc’s lesser estates have the Cru Bourgeois system, which after many iterations now awards annual quality labels and a tiered ranking (including “Cru Bourgeois Exceptionnel”) on a rolling basis. All of these systems highlight one fact: Bordeaux is wedded to the idea of hierarchy and classification, yet the 1855 classification stands apart as a singular relic – one that by its permanence offers clarity and tradition, even if at the cost of being outdated.

Legacy and Long-Term Significance

The legacy of the 1855 Bordeaux classification is a study in how a moment in history can ripple forward to shape an entire industry. For Bordeaux’s left bank, 1855 established a enduring framework of prestige that has proven remarkably resilient. It conferred a form of cultural patrimony: each Grand Cru Classé estate became not just a private business but a guardian of Bordeaux’s heritage. Owners of classed growths over the years have often spoken of their responsibility to uphold the high standards befitting their rank. This sense of legacy can be a motivator – as seen in the investments and improvements that many estates made in the late 20th century to live up to (or exceed) their classification. Even those who criticize the classification’s rigidity often acknowledge that it has helped preserve a certain continuity and excellence among the top châteaux. The stakes of being a First Growth or a Second Growth are such that proprietors know they are being judged not just against their neighbors, but against history.

Moreover, the classification has had significant economic and structural consequences. It concentrated interest and wealth in the Médoc, particularly in the four communes most represented (Margaux, Saint-Julien, Pauillac, Saint-Estèphe). These areas benefited from their châteaux’ grand cru status, attracting better prices and investment. It wasn’t until much later in the 20th century that non-classified properties in the Médoc or top estates in other Bordeaux regions could begin to approach the cachet of the 1855 elites. In effect, 1855 created a two-tier society: the classed growths and the rest. This spurred some outsiders to excellence out of rivalry, but it also meant many fine estates languished in relative obscurity simply because they weren’t on “the list.” The advent of influential wine critics in the late 20th century (like Robert Parker) somewhat leveled the playing field by highlighting quality wherever it was found, classification be damned. Yet even today, a newcomer estate making a superb wine will inevitably be compared to classed growth benchmarks, and if it’s in the Médoc, people might dub it a “future candidate for classification” – hypothetically, since no new candidates are considered.

Culturally, the 1855 classification endures as part of the mythology of Bordeaux. It is frequently referenced in literature about wine, taught to students of oenology and wine business, and used as an easy entry point for consumers to understand Bordeaux’s tiered system. Generations of wine lovers have memorized the First Growths as if learning a poem, and debate about the merits of various Second or Third Growths is a staple of connoisseur conversations. The very fixation on whether a certain estate is “underrated for a Third Growth” or “outperforming its Fourth Growth status” shows how the classification remains a touchstone – a common language for discussing Bordeaux wine quality.

And yet, there is an inherent tension in venerating a 170-year-old market ranking as a modern arbiter. Some critics argue that clinging to 1855 has bred complacency at times, or at least an overemphasis on status. The counterargument is that the classification’s permanence has also preserved an identity and incentive: the classed growths know they have something precious to lose (their reputation, even if not their title) if they fail to maintain high standards. Indeed, since the 1980s, one can observe a general renaissance among the classed growth châteaux – extensive replantings, better vineyard management, modernization of cellars – leading to an overall rise in quality that arguably keeps the classification relevant. It is telling that in blind tastings, one often still finds a strong correlation between an estate’s 1855 rank and the wine’s assessed quality, especially among the top tiers. This suggests the classification, for all its flaws, captured an alignment of great terroir and human excellence that has proven enduring. The best sites of the Médoc identified long ago are, by and large, still the producers of the best wines today.

Conclusion

The 1855 Bordeaux classification stands as a monument in wine history – one carved out of the economic realities of its time, subsequently weathered by history, yet fundamentally unaltered in form. It has been called a “living fossil,” a “golden cage,” and even “a necessary fiction.” All these characterizations acknowledge the central paradox: what began as a pragmatic ranking of wines for an exposition became an almost immutable article of faith in Bordeaux. For the wine enthusiast or scholar, understanding the 1855 classification is essential to understanding Bordeaux. It is the key to the region’s grand cru culture, its market structure, and much of its terminology. At the same time, a critical perspective requires recognizing that the classification is not sacrosanct truth handed down from on high; it was a human construct, with built-in limitations and biases reflective of 1855, not 2025.

Is the classification still relevant? The answer lies in what one values. As a historical artifact and marketing framework, it is undeniably relevant – it continues to shape prices and perceptions. As a strict qualitative ranking, it is imperfect – some would say increasingly out of step with reality. Bordeaux’s genius, however, has been to let the classification endure while finding informal ways to adapt. The rise of excellent unclassified wines has broadened the landscape without formally toppling the old order. In practice, merchants and consumers now recognize a de facto “seventh growth” or “virtual classification” of estates outside the 1855 list that merit attention. In parallel, the 1855 classed growths strive to prove each vintage that their inherited titles are still deserved.

For the foreseeable future, it is likely that the 1855 classification will remain unchanged. It has survived wars and crises; it can certainly survive modern scrutiny. The debate over it – whether championing its authority or calling for its overhaul – is itself a healthy part of Bordeaux’s discourse. Such tension between tradition and progress is at the heart of wine’s evolution. The 1855 classification, product of an imperial age, persists as both bedrock and lightning rod. It offers us a direct link to the past and a framework to discuss the present. And for the connoisseurs, collectors, and critics who form Bordeaux’s global audience, that may be its most valuable role: a foundation from which to appreciate not just what has stayed the same in great wine, but also what has changed, bloomed, or emerged anew outside its venerable borders.