Bacchus in Gaul: The First Millennium of French Wine

From Celtic beer lands to monastic vineyards: how Romans, dark-age resilience, and the Church forged French wine, 600 BCE–1000 CE.

Introduction

French wine culture reaches back over 2,600 years – to an era long before “France” existed as a nation. In antiquity, the land that would become France was known as Gaul, populated by Celtic tribes with no native winemaking tradition. Yet by the year 1000 CE, Gaul’s transformation into a wine-producing heartland was essentially complete: vineyards stretched from the sunny Mediterranean coast to the cool Paris basin, tended by a patchwork of Gallo-Roman farmers, Frankish nobles, and monastic estates. This article explores how wine was introduced to ancient Gaul and how viticulture spread and endured through the upheavals of the first millennium. We examine not only what happened – the key people, places, and policies – but why these developments mattered. Over centuries, wine in Gaul evolved from exotic import to everyday staple, from a mark of the “civilized” world to an integral pillar of French culture and identity. Crucially, many of the structures and traditions that define French fine wine today – revered terroirs, regional styles, even nascent quality controls – trace their origins to this formative era. The story that follows is rooted in reliable evidence from archaeology, historical texts, and estate records, with uncertainties acknowledged where the record is fragmentary. Far from a romantic legend, the early history of French wine is a tale of cultural adaptation, economic ambition, and resilient continuity through dark ages – a foundation upon which later centuries of French winemaking prestige were built.

Before the Romans: Wine Reaches Celtic Gaul

In the Iron Age centuries prior to Roman conquest, the Celtic peoples of Gaul were primarily beer- and mead-drinkers, unfamiliar with viticulture. Wild grapevines grew in parts of Gaul, but there is no evidence the Celts made wine from them; instead, they fermented grains and honey for alcohol and regarded wine as an imported luxury. To the wine-loving civilizations of the Mediterranean – notably the Greeks and Etruscans – this made the Gauls “barbarians” in the classical eye. Wine was a hallmark of Greco-Roman civilization, and introducing it to Gaul was seen as both a civilizing mission and a lucrative opportunity.

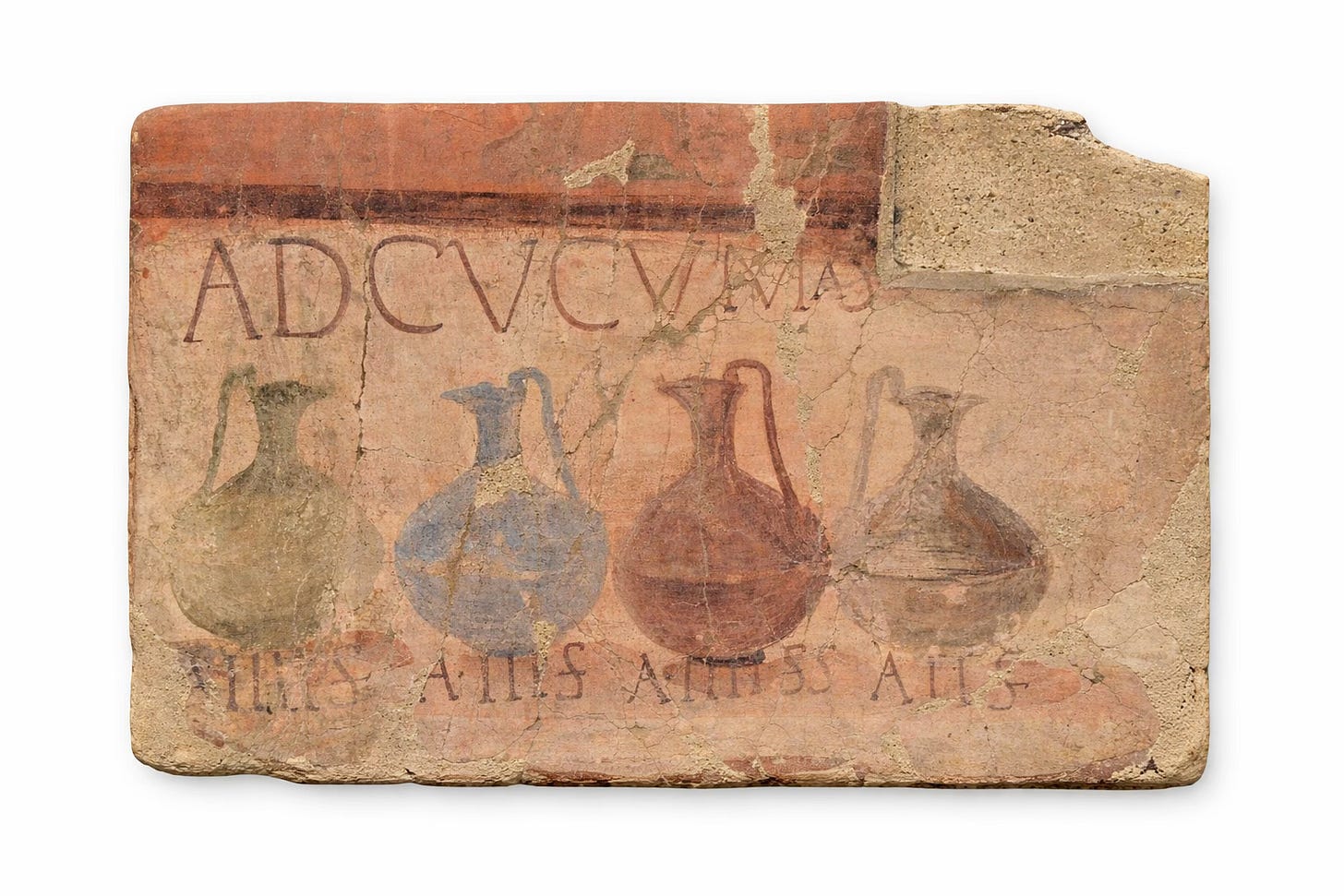

The first wines to reach Gaul arrived via maritime trade. By the 7th–6th centuries BCE, Etruscan merchants from Italy were shipping wine in amphorae to trading posts on the southern Gallic coast. Archaeologists have found Etruscan wine amphoras from this period at ancient coastal sites like Lattara (near modern Montpellier), indicating a taste for imported wine among the Celtic elite. A watershed came around 600 BCE, when Greek colonists from Phocaea (in today’s Turkey) founded the city of Massalia (Marseille) on the Mediterranean shore. The Greeks, for whom wine was an everyday necessity, brought vines and winemaking know-how to this new outpost. By about 525 BCE the Massaliotes were not only importing wine but producing it locally – we know this because excavations show Massalia began manufacturing its own clay amphorae by that date, presumably to fill with indigenous wine. Grape seeds and planting sites from the 6th–5th centuries BCE have been discovered around Marseille and inland at places like Nîmes. This points to the very birth of French viticulture: by 500 BCE, wine was being made on what is now French soil. Local production quickly undercut the earlier Etruscan wine trade, though Etruscan imports via Lattara persisted for a time as vineyards spread slowly beyond the Greek settlements.

From the start, wine in Gaul was associated with social prestige and foreign sophistication. A famous archaeological find underscores this dynamic: the “Vix krater,” a massive bronze Greek wine-mixing vessel over a meter tall, buried around 500 BCE in the tomb of a Celtic noblewoman in Burgundy. This lavish object – far larger than a practical punchbowl – was likely a status symbol rather than for everyday use, but it was found alongside other imported Greek wine paraphernalia (pitchers, drinking cups). The Vix krater vividly illustrates that by the late Iron Age, wine had become a prized indulgence among the Gallic aristocracy, acquired through trade with the Mediterranean world. In effect, wine arrived in Gaul as a marker of elite culture under Greek influence. For the Celts, it was an alien beverage imbued with the allure of the classical world – something worth acquiring at great cost. Indeed, classical authors recount that unscrupulous Italian traders exploited the Gauls’ thirst for wine: one ancient chronicler noted that merchants would sometimes exchange a single amphora of Italian wine for a Gaulish slave. Beyond slaves, wine even served as currency to obtain iron, copper, and other commodities, with records of wine being traded for the output of entire mines. Such accounts (likely exaggerated but based in truth) highlight how novel and coveted wine was in pre-Roman Gaul – a luxury good, social lubricant, and civilizing symbol all in one.

Roman Conquest and the Spread of the Vine

The Roman annexation of Transalpine Gaul in the late 2nd and 1st centuries BCE transformed the trajectory of French wine. Once Rome took control – first of the Mediterranean Narbonensis region in 125 BCE, then of the rest of Gaul by Julius Caesar’s campaigns of the 50s BCE – the stage was set for a vast expansion of viticulture. Initially, however, the Romans treated Gaul more as a wine market than a wine producer. In the early decades of Roman rule, Italian vintners flooded Gaul with imported wine, principally from Italy’s premier vineyards in Campania. Archaeologists have unearthed “hundreds of thousands” of Italian wine amphorae in Gaul – scattered from the Rhône Valley to the Loire, and from Narbonne to Bordeaux. These amphora finds map the contours of a booming import trade. For instance, concentrations of 1st-century BCE Campanian amphorae appear around inland towns (Autun, Roanne, Chalon-sur-Saône) and Atlantic ports (Nantes, up the Loire to Angers), indicating distribution networks reaching deep into Gaul. Even in the southwest, amphoras bearing the stamp of a Pompeian wine exporter named Porcius have been found near Toulouse, Agen, and Bordeaux – evidence that Roman wine was penetrating areas that had not yet begun growing their own grapes. By the height of the Late Republic (c.50 BCE), Rome was exporting extraordinary volumes: an estimated twelve million liters of wine per year were shipped from Italy to Gaul between 150 and 25 BCE. This far exceeded what the small Roman settler population and garrisons in Gaul could consume, implying a robust local demand among the Gauls themselves. In effect, Gaul had become a profitable wine frontier for Italian merchants. Some of this imported wine was even re-exported: historians surmise that a portion of the Italian wine landed at Bordeaux was sent onward to supply Roman Britain, foreshadowing the later medieval wine trade from Bordeaux to England.

However, the Romans soon realized that Gaul could do more than just buy wine – it could grow it. Climatically and agriculturally, much of Gaul was suitable for vines. The Roman authorities had initially been cautious: a decree of the Senate around the founding of Narbonne (c.118 BCE) reportedly forbade the native “Transalpine” Gauls from planting vineyards or olive groves, aiming to safeguard Italian exports. But this restriction applied to the indigenous population; it did not stop Roman colonists in Gaul from cultivating wine. As veterans and settlers fanned out in the new province, they carried vine cuttings with them. By the end of the 1st century BCE, Romans had begun systematically planting vineyards in southern Gaul – first along the Mediterranean coast and lower Rhône, then progressively farther inland. Roman agronomists wisely chose terrain that mirrored the hill-dominated vineyards of Italy. They “favoured hill sites (no use for grain production) for their vines”, as one historical geographer notes. High ground with poor soil was ideal for grapes and posed no competition with cereal farming. Thus, hillside terroirs in places like the foothills of the Cévennes (around Gaillac) and the Rhône Valley slopes were among the earliest viticultural sites beyond the coast. The choice of these locations was no accident: Gaillac, for example, lay at a strategic nexus – offering suitable slopes and a navigable river (the Tarn flowing into the Garonne) to carry wine to the Roman garrisons further north. In the view of modern historians, Roman Gaul’s first “fine wine” regions were likely Gaillac in the southwest and the area around Vienne in the northern Rhône. These two zones, blessed with transport routes and attentive Roman cultivators, developed reputations for quality wine that eclipsed other Gallic regions for centuries. (By contrast, areas like Burgundy or much of Bordeaux were still backwaters for viticulture at this stage.) Roman soldiers on the frontier – and perhaps even the imperial tables in Italy – began to taste wines grown on Gallic soil.

Within two centuries of Roman rule, the vine had spread to “all the environmental niches it could occupy” in Gaul. By the 1st century CE, vineyards were thriving not just in Mediterranean Gaul but in the interior and western regions as well. One notable early venture was at Gaillac, northeast of Toulouse: as mentioned, amphora workshops there and praise from writers like Cicero (who noted the “Toulouse wine trade” around 50 BCE) attest that Gaillac’s wines were already commerce-worthy in the late Republic. Romans in Bordeaux in those days actually drank Gaillac wine, since Bordeaux’s own vines had yet to be planted. (Indeed, Gaillac and neighboring areas supplied much of Bordeaux’s wine well into the Middle Ages.) Another cradle of Gallic viticulture was the Rhône Valley. Near Vienne (just south of Lyon), Roman colonists established vines early; by the 1st century CE, the naturalist Pliny the Elder was noting vineyards in that area. The Rhône wine that most impressed Romans was made from a grape they called Allobrogica – an indigenous variety named for the local Allobroges tribe. The agronomist Celsus, writing in the first decades of the 1st century CE, praised wine from vinea allobrogica, implying the grape had already been cultivated for generations. Allobrogica was a late-ripening black grape well adapted to the cooler climate of the far north of Roman Gaul: remarkably, it could be left on the vine through the first autumn frost and still yield sound wine. Such frost-endurance would have been unthinkable in Italy, but in Gaul it allowed greater hang-time and flavor concentration in the grapes. Roman connoisseurs appreciated the result – a famous wine called Picatum (meaning “pine-scented”), which took on a resinous note from the pine pitch used to seal its amphorae. Picatum from the Rhône is mentioned in accounts of imperial banquets, suggesting it traveled to Rome as a valued regional specialty. Modern oenologists speculate that Allobrogica may survive today in the DNA of French grapes (it was likely related to, or the ancestor of, the alpine variety Mondeuse and thus a forebear of Syrah). In the southwest, meanwhile, the Romans cultivated a grape called Biturica around Bordeaux – possibly named after the Bituriges Vivisci tribe. Biturica was likely an imported vine (perhaps brought from Spain’s Basque country) that proved well-suited to Bordeaux’s damp Atlantic climate. Intriguingly, ampelographers have identified Biturica as an ancestor of the Carmenetfamily of grapes – which includes none other than Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc, two linchpins of modern Bordeaux wine. Thus, Roman vintners not only planted vines across Gaul, they unwittingly laid the genetic groundwork for key French grape varieties to come.

By the time the Western Roman Empire began to falter in the 5th century, Gaul was firmly established as a wine country. “By 500, when Roman domination of Gaul ended, wine production had been established in what are now France’s best-known wine regions: Bordeaux, the Loire and Rhône valleys, Alsace, Champagne, and Burgundy”. In other words, virtually all the terroirs that today define French fine wine – from the chalky slopes of Champagne to the limestone of Burgundy and gravel of Bordeaux – were already under vine to some extent by late antiquity. This remarkable diffusion was accelerated by Roman enterprise but also moderated by Roman policy. The imperial government occasionally intervened in the wine trade, providing an early precedent for regulating French viticulture. A famous example came in 92 CE, when Emperor Domitian issued an edict responding to a wine glut and declining grain production. Domitian’s decree “ordered the grubbing up of half the vines in Gaul and [the Empire’s] other provinces outside Italy” and forbade any new vineyard plantings in those areas. Ostensibly, the aim was to curb overproduction and protect arable land for cereals – and perhaps to shield Italian winegrowers from provincial competition. This drastic measure, which would have slashed Gaul’s vineyard area, marks the first known instance of state intervention in French wine history. In hindsight it foreshadows many later efforts (medieval to modern) by authorities to control quality and balance supply and demand in the wine sector. In practice, however, Domitian’s edict may have been largely ignored in Gaul – the archaeological record shows no clear collapse of Gallic viticulture in the 2nd century. Over a century and a half later, in 280 CE, Emperor Probus formally repealed Domitian’s ban. Probus – himself born in wine-rich Pannonia – not only lifted restrictions but actively “gave the Celts the freedom to plant vines and make wine”, perhaps hoping to win the loyalty of Gaul and other provinces amid mounting barbarian pressures. By that point, the legal change probably just acknowledged reality: Gaul’s vineyards had kept expanding regardless of the old edict. Still, Probus’s pro-vine decree in 280 CE cleared any remaining ambiguity and encouraged viticulture to continue its march northward and westward. By the late 4th century, vineyards could even be found on the far fringes of Gaul’s cool climate – as far north as the region around Paris and the chalk plains of Champagne. The geographic spread that Roman wine culture achieved in Gaul is truly impressive. Not only did the Romans introduce winemaking to Gaul, but they also ensured it took permanent root across vastly diverse landscapes – from the sun-baked Mediterranean coast to the foggy banks of the Marne.

Equally important, the Romans inculcated in the Gauls a set of attitudes toward wine – economic, social, and aesthetic – that would resonate through French history. Wine had become a commercial engine: under Roman rule it was Gaul’s most profitable agricultural product, so valuable that until the 3rd century it was legally reserved for Roman citizens to produce (a monopoly only lifted by Caracalla’s edict of 212 CE granting citizenship to most free Gauls). Wine was also firmly embedded as a daily beverage and social lubricant, preferred over the “barbaric” beer. We see the Gallo-Roman population integrating wine into all levels of society. For the colonists and urban elite, wine culture meant emulating Roman refinement – from the measured convivium (dining party) with diluted wines, to the collection of prized vintages in villa cellars. For the native peasantry, wine growing and drinking gradually became part of local life too, though likely in simpler forms. Roman commentators such as Posidonius and Diodorus noted the Gauls’ enthusiastic adoption of wine – sometimes to intemperate extremes – which the Romans alternately found amusing and alarming. The Gauls, unused to the potency of wine, were said to drink it unmixed and “give themselves up to the pleasure without restraint,” in one ancient account. This stereotype of the hard-drinking Gaul would later give way to a more nuanced reality as Gallo-Roman society matured. In any case, by the twilight of the Roman era, Gaul was producing enough wine not only for local consumption but even to export modestly (as evidenced by Gallic amphorae found in Roman Britain and along the Rhine). The once one-way flow of wine from Italy had turned into a two-way commerce. In 79 CE, when a cataclysmic eruption of Mt. Vesuvius devastated vineyards around Pompeii, Italian merchants actually imported Gallic wine to fill the shortfall, shipping barrels of Gaul’s vintage down to Rome’s port at Ostia. It was a fleeting reversal of roles, but symbolically significant: the former wine frontier had become a capable wine supplier in its own right. In short, four centuries of Roman rule gave Gaul not only vines and wines, but also a lasting conviction that wine was the lifeblood of civilized life. This conviction would endure even as Rome’s political power waned.

After Rome: Survival and Adaptation in the Early Middle Ages

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century plunged Gaul – now ruled by a patchwork of Germanic kingdoms – into political turmoil. One might expect such instability to have devastated viticulture. Long-distance trade shrank, cities contracted, and literacy (hence record-keeping) declined, all factors that could undermine a complex agricultural enterprise like winegrowing. Yet the evidence suggests that wine production in Gaul proved surprisingly resilient through the so-called Dark Ages. Archaeological and textual clues, though sparse, indicate remarkable continuity, even growth in some locales, as new peoples settled into the structures Rome left behind. Crucially, the incoming barbarian elites shared the Roman taste for wine and often took pains to protect and maintain vineyards in their domains. For example, the Visigoths – who ruled much of southwest Gaul (Aquitaine) in the 5th–6th centuries – incorporated strict protections for vineyards into their law codes. Damaging someone’s vines was met with severe punishment under Visigothic law, implying that these new rulers understood the high value of the vineyards they’d inherited from Rome. In practice, the Visigoth kings of Toulouse did not uproot the thriving wine culture of Aquitaine; if anything, they patronized it. We even see continuity in vineyard ownership: the great Gallo-Roman villa estates, many with their own vineyards, often passed intact into the hands of the new Gothic nobility, who had every incentive to keep the wine flowing. Similar patterns held in Burgundy and the Loire region under the Burgundians, and later in Provence under the Ostrogoths – conquering elites adopting the existing wine economy rather than destroying it.

To be sure, the collapse of centralized Roman authority did disrupt the scale and distribution of the wine trade. Without the Empire’s vast market and roads, Gaul’s wine economy became more localized in the 5th–7th centuries. The export of wine beyond local regions diminished; for instance, the once-thriving pipeline sending Aquitanian wines to northern Gaul and Britain dried up as Roman trade networks fell apart. Some marginal vineyard areas that had been planted mainly to serve distant markets (perhaps fringe sites in favor of grain or areas far from consumption centers) may have been abandoned during warfare or economic stress. There are isolated anecdotes of vineyards being deliberately destroyed in conflict – for example, when the Frankish armies defeated the Visigoths at the Battle of Vouillé in 507, sources later claimed the victors ravaged the enemy’s vines in revenge. But such instances were exceptions. Overall, by the time the Frankish kingdom (the Merovingians) consolidated power over Gaul in the 6th–7th centuries, the vineyards established in Roman times were largely still there, providing wine to local lords and communities. In some regions, viticulture even expanded during the early medieval period. Burgundy is a notable example: here, there is evidence that woodland was cleared to plant new vineyards as early as the 6th–7th centuries. The Burgundian realm, and later the Frankish dukes of Burgundy, actively encouraged vine planting, seeing the economic benefit. By the Carolingian era (8th–9th centuries), Burgundy’s Côte d’Or slopes were well on their way to becoming a viticultural heartland. Farther north, in the Paris basin and Champagne, the spread of vineyards followed the power centers of the new Frankish elite. Paris itself, though not yet the capital it would become, had vineyards on its outskirts by the early medieval period. As one historian succinctly summarizes, “By the end of Roman Gaul, vineyards could be found all over [the land], as far north as Paris and Champagne”, and that pattern largely persisted despite the ensuing chaos.

One of the most important factors ensuring wine’s survival in post-Roman Gaul was the rise of the Christian Church as the dominant social institution. Christianity not only accepted wine; it sanctified it. The Eucharistic sacrament required wine for Mass, giving the drink a hallowed role in Christian ritual. This meant that any Christian realm needed a reliable source of wine, even if only for liturgical purposes. In reality, the Church’s embrace of wine went far beyond sacrament. By the early Middle Ages, every monastery, cathedral, and convent aspired to own vineyards, both to supply their religious needs and to generate income or sustenance. Monastic orders, in particular, would come to be seen as the guardians of viticulture – a somewhat romanticized view, but not entirely unfounded. As early as the 6th century, we see monastic viticulture taking root in Gaul. Around 543 CE, Saint Maurus (a disciple of St. Benedict) established one of Gaul’s first important monasteries at Glanfeuil on the Loire River near Angers. Little detail survives about this monastery’s activities, but later tradition holds that it was here that the grape variety Chenin Blanc was first cultivated. Chenin Blanc, a white grape now emblematic of the Loire Valley, may indeed have monastic origins – an intriguing example of how medieval monks might have selected and spread superior cultivars. More concretely documented is the spread of the Rule of St. Benedict in Frankish Gaul during the 6th–7th centuries, which shaped monastic life and attitudes towards wine. St. Benedict’s rule (written c.540 for Italian monasteries) took a realistic stance on wine: while ideally monks would practice abstinence, Benedict recognized that “nowadays monks cannot be persuaded” to forgo wine entirely, and therefore allowed each monk a moderate daily ration (about one hemina, roughly 0.3 liters). This concession was born of practicality – to prevent worse excesses – and Benedict sternly warned against drunkenness or “drinking to satiety”. The Rule’s nuanced position shows how integral wine had become even in ascetic circles: it was considered a normal part of diet and fellowship (in monastic refectories), yet its dangers were well recognized. Monasteries were to drink “temperately” and value wine’s spiritual symbolism over its sensory pleasures. Still, the inclusion of a daily wine allowance in a foundational monastic text underscores that by the 6th century, wine was seen as a staple of life in Gaul – for laypeople and clergy alike – albeit a gift to be used with discipline.

As the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties solidified a new Frankish order (roughly 6th to 9th centuries), wine production in France not only persisted but aligned itself with the emerging power structures. Three main groups held vineyards in this era: the Church, the nobility, and to a lesser extent the crown. Royal influence varied – Charlemagne and his successors did issue decrees encouraging estate managers to maintain vines (the famous 9th-century Capitulare de villis lists vineyards among the assets each royal manor should cultivate), but in practice kings directly controlled only a fraction of wine production. It was the great lords and prelates who truly kept the wine industry alive. The Frankish aristocracy, much like the Gallo-Roman gentry before them, prized good wine as part of noble living. We read of Carolingian-era magnates boasting of their vineyards and the fine quality of their personal wine. In fact, in the 9th century, having productive vineyards was such a mark of status that some powerful rulers in Germanic lands were eager to acquire estates in Burgundy or around Paris specifically “for the abundance of wine” those lands yielded. Wine had become a symbol of prosperity and prestige among the medieval elite, just as it had been for Romans – a continuity of attitude across the rupture of empire.

The Church, for its part, emerged as arguably the single biggest landowner of vineyards by the end of the first millennium. Monasteries and bishoprics steadily accumulated vineyard lands through royal grants, pious donations, and their own pioneering efforts in clearing and planting. Major monastic institutions founded during the 7th–9th centuries across France all planted vines if the climate allowed. For example, Champagne – now famous for its bubbly wine – was already a significant wine region in the early medieval period partly thanks to monastic development. Numerous great abbeys were founded in Champagne in the 600s (including, notably, the Abbey of Hautvillers, which much later would be associated with Dom Pérignon) and “all of them planted vineyards” to make the still wines of the region. By the early 9th century, Champagne’s vinous output was noteworthy enough that distinctions were being made between different districts’ wines. In 816, when Emperor Louis the Pious (Charlemagne’s son) was crowned at Reims, the assembled nobility enjoyed ample quantities of the local vintage. Thus, long before “Champagne” became synonymous with sparkling wine and royal fêtes in the modern era, the region’s wines had acquired an aura of prestige through their role in the coronation feasts of Frankish kings. This early royal patronage would echo through history, reinforcing the notion that wines of Champagne are fit for kings.

Beyond Champagne, every corner of Francia where grapes could grow saw church involvement. The Council of Aachen in 816 – a reform synod under Charlemagne’s son – went so far as to decree that each cathedral must maintain a school of clergy (canons) whose duties included tending cathedral vineyards. This illustrates institutional commitment: viticulture was officially woven into the ecclesiastical infrastructure of the Carolingian empire. From the great wine regions like Aquitaine and Burgundy to marginal northern outposts, bishops and abbots cultivated vines. Often we find that a bishopric’s prestige was tied to its wine. The Bishop of Tours, for instance, had vineyards under his control, and bishops of Coutances, Soissons, Langres and others are noted in chronicles for either planting vines or receiving vineyards as gifts. Wine was also a common form of tithe and tribute. Churches and monasteries received barrels of wine from local farmers as part of annual dues, and wealthy nobles endowed religious houses with vineyards to ensure prayers for their souls (and perhaps to secure a heavenly supply of wine!). A 7th-century example: the Bishop of Cahors (in southwest France) sent ten barrels of Cahors wine to the Bishop of Verdun – a generous gift of a local product traveling across the fractured kingdom. Even earlier, Gregory of Tours, a 6th-century historian-bishop, tells of a devout widow who showed her piety by bringing a measure of wine to her church every day. When this widow died, her testament reveals the extent of private vineyard ownership still outside the Church: she bequeathed numerous vineyards – dividing them among eighteen different heirs including members of her household and local churches, and even granting one plot to an emancipated slave. This single anecdote speaks volumes: it shows that substantial vineyards remained in secular hands (in this case, a Gallo-Roman noble family’s estate) and that wine lands were valuable enough to feature prominently in wills. It also illustrates how vineyards often passed from lay ownership into ecclesiastical hands via pious donation (some of her vines went to churches). Over time, such bequests made the Church a dominant vineyard proprietor, though we should not assume monks were the only winemakers. Many vineyards “were owned by nobles and other wealthy secular proprietors” throughout this era, producing wine for their own consumption and local markets. The reason our records mention church vineyards more frequently is simply that literate churchmen kept better accounts; the silence of the sources on many private vineyards does not mean they did not exist. In fact, historians caution that monastic chronicles likely overemphasize monastic contributions, whereas a great deal of viticulture continued on private estates, handed down through generations of lords and peasant communities.

What is beyond doubt is that the Church became a vital engine of continuity and improvement in winegrowing. Monasteries provided stability, expertise, and networks of knowledge exchange. By the 9th and 10th centuries, Benedictine and other orders had developed disciplined viticultural practices. Some abbeys even implemented early quality controls reminiscent of appellation rules – an example slightly after 1000 is the Abbey of Saint-Michel in Gaillac, where monks later established detailed ordinances for how their esteemed wine should be made, down to stipulating only pigeon manure could be used as fertilizer. The fact that medieval monks bothered to codify such rules indicates that certain wines had reputations to uphold, a proto-appellation system driven by pride and commerce. In Gaillac’s case, this would happen in the 12th–13th centuries, but its roots lie in the recognized quality of that terroir since Roman times, preserved through the Dark Ages by local cultivation and monastic record-keeping. We see similar threads in Burgundy: by the late 6th century, the Abbey of Saint-Germain at Auxerre and others in Burgundy were accumulating vineyards, setting the stage for Burgundy’s later rise to renown. In the Rhône, the Church owned vineyards in the Côte Rôtie area by the time of the Carolingians, continuing the legacy of the Allobrogica grape. And in the Loire, abbeys like Marmoutier (near Tours, founded by St. Martin in the 4th century) maintained vineyards that produced the ancestor of today’s vins de Touraine.

The early medieval period also shaped how wine was used and perceived culturally. Without the cosmopolitan buzz of Rome’s cities, wine found a new centrality in the local and spiritual spheres. It was consumed at the lord’s table and the monk’s refectory; it oiled the wheels of hospitality and diplomacy. A noteworthy social function of monastic vineyards was to provision travelers. Many monasteries served as rest houses for pilgrims, envoys, and officials crisscrossing the realm. These guests expected refreshment. Contemporary accounts note that “travelers who stopped and rested at monasteries expected to be fed and provided with wine,” as did visiting kings, nobles, and bishops with their often “thirsty retinues”. Serving good wine became a point of honor for religious hosts. Monastic cellarers thus had reason to press for quality and adequate quantity in their production. Monasteries and abbeys also hosted feasts on holy days and accommodated local gatherings – again occasions where wine was central. Meanwhile, secular courts of the Merovingian and Carolingian kings featured wine in ceremonial banquets and daily life, though beer and other drinks remained common for the lower classes. Over the early medieval centuries, one observes a sharpening dual awareness regarding wine: on one hand, it was prized as a blessing (nutritive, joyful, even divinely ordained in scripture), and on the other hand, its misuse was castigated as a source of vice. The Church had to continuously preach moderation. As early as the 6th century, church synods and bishops like Saint Caesarius of Arles thundered against the evils of drunkenness – a vice to which both peasants and warriors were prone. But interestingly, some Church Fathers developed the mystical concept of “sobria ebrietas” or “sober intoxication,” referring to the spiritual rapture that could accompany the moderate enjoyment of wine. This idea tried to reconcile the uplifting, even ecstatic sensation of a mild wine buzz with religious propriety: if done in moderation, the drinker’s joy could be likened to a holy fervor rather than sinful excess. It was a theologically subtle endorsement of temperate drinking. Nonetheless, the official stance remained that overindulgence was sinful. Repeated church councils denounced heavy drinking among clergy and laity alike. Importantly, the Carolingian-era Church’s efforts to curb alcohol abuse – while encouraging wine’s healthy use – represent an early precursor of the French ethos of moderating wine consumption for the sake of social order and health. This ethos, balancing wine’s benefits against its dangers, would periodically re-emerge (for example, in medieval monastic rules, in the 19th-century temperance movements, and even in modern public health dialogues). Such continuity underscores how deeply wine had become embedded in French society by 1000 CE: it was simultaneously an agricultural commodity, a cultural treasure, a spiritual symbol, and a moral test.

By the Year 1000: Foundations of a Wine Culture

As the first millennium CE drew to a close, the landscape of French wine was poised for a new chapter – but one firmly rooted in the achievements of the past centuries. Around the year 1000, Europe experienced a convergence of favorable conditions. The climate was entering a mild phase (the Medieval Warm Period), bringing longer growing seasons in Northern Europe. This climatic upswing, beginning in the tenth century, meant that marginal vine-growing areas in France (such as higher elevations and more northerly latitudes) could ripen grapes more reliably. Better weather, coupled with a slow rebound in population and commerce, set the stage for a great expansion of viticulture in the High Middle Ages. Indeed, from the 11th century onward, Europe would see a wine boom – the planting of vineyards in new lands, the rise of great crus and appellations, and the export of French wines to all corners of the known world.

Yet none of that subsequent florescence would have been possible without the groundwork laid between antiquity and 1000 CE. By 1000, France’s fundamental wine geography was established. The same regions that Romans had identified as propitious – Bordeaux, Burgundy, the Rhône, Loire, Champagne, Alsace, Provence, Languedoc – were still the core wine provinces under the Capetian kings (the dynasty that began in 987). Not only were they established; many were already specializing and differentiating. We have seen how Champagne in the early 9th century was recognized for its local wine at royal coronations, how Gaillac and the Rhône had long-standing reputations going back to Roman esteem, and how Burgundy’s vineyard area had actually expanded under monastic and ducal patronage. Even the relative latecomers like the Loire Valley were catching up – vineyards around Orléans, Tours, and Nantes are attested by the 6th–7th centuries, with evidence of wine presses near Tours dating to the Roman era and reports by Gregory of Tours of viticulture in coastal Nantes by the 580s. By 1000, the Loire wines (including what would later be Anjou, Saumur, etc.) had a foothold, possibly initially fostered under protection of the early Plantagenet counts and local bishops. Meanwhile, the far southwest – Bordeaux and Gascony – had weathered centuries of turmoil (from Germanic invasions to Viking raids) and was entering the High Middle Ages with Bordeaux poised to re-emerge as a trading port. Viking depredations in the 9th century had temporarily emptied Bordeaux (the Northmen “virtually abandoned” the city after sacking it), but with the Viking threat receding by the tenth century and order gradually restored, the Bordeaux region would soon revive its latent advantage: access to the Atlantic for wine export. Already by the late Carolingian era, there are hints of wine commerce restarting – the Norse themselves, paradoxically, had been carrying wine off for their own use and even trading it. In Normandy, which a Viking leader (Rollo) settled in 911, the new Norman lords took to local wine and by the 11th century Normandy was another market for wines shipped up the Seine from Burgundy and Champagne.

Politically, the fragmentation of Charlemagne’s empire into feudal lordships (formalized by the tenth century) actually benefited local winegrowing. With power decentralized, regional lords and monasteries had autonomy to cultivate and promote their own vinous specialties. In the absence of a strong central authority, economic initiative bubbled up from below. Lords sought to enrich their domains – planting vineyards if none existed, or improving those they had – both for profit and to enhance their table. Monasteries, now increasingly independent after the reforms of Cluny (founded in 910), competed in a pious way to make the best wines for God’s glory (and their guests’ satisfaction). By the late 11th century, the great abbeys of Burgundy (Cluny, Cîteaux) would control vineyards that later became world-famous clos. All of this was made possible by the unbroken thread of viticultural knowledge from Roman times through 1000. Techniques of vine pruning, vintage timing (the medieval institution of the ban des vendanges – the official start of harvest – actually began in this era to ensure grapes were picked at optimal ripeness), and winemaking (fermentation in wooden barrels rather than clay jars, an inheritance from the Gauls who invented the barrel) were passed down or rediscovered on the foundations laid in earlier centuries. For example, the use of wooden barrels – adopted during the Roman-Gaul period by the 3rd century – had by 1000 CE long replaced amphorae, enabling larger-scale storage and overland transport of wine (albeit depriving historians of easy archeological evidence, since barrels decay). The basic wine styles were also largely continuous: deep red wines in the south, lighter or honey-hued wines in the north; sweet or flavored wines (using herbs or tree resins) continued to be made alongside pure grape wine; and strong preserved wines (perhaps akin to later vins doux naturels) were appreciated for longevity. These traditions would all evolve, of course, but the point is that nothing “new” had to be invented after 1000 for France to assert itself as a wine superpower – the medieval French simply had to build upon the rich legacy they had inherited.

In summary, by the close of the first millennium, France – though not yet a unified kingdom in the modern sense – had irreversibly become wine country. The vine had survived conquests, migrations, climate swings, and religious upheavals. It had become entwined with French soil and society: a guarantor of nutrition and pleasure, a commodity of exchange, an object of regulation, a gift to the Church, and a source of local pride. The achievements and struggles of this era set in motion several long-term currents in French wine history. One was the concept of terroir – even if not articulated as such, the Romans and medieval growers learned through trial and error which plots produced the best wine, whether the hill of Hermitage in the Rhône or the limestone côte of Beaune. The preference for certain sites, and the differential reputation (and price) of wines from various districts, was already evident by 1000 (as seen in the esteem for places like Gaillac or Reims). Another was the tension between quantity and quality: Domitian’s ancient edict and the Church’s statutes against drunkenness both aimed to control excess, reflecting an understanding that quality wine comes from restraint – in production or consumption – a philosophy later embodied in France’s Appellation Contrôlée system and cultural norms around drinking. A third was the alliance of wine with social and spiritual authority: from the Roman patrician to the feudal lord to the abbot and bishop, leadership in French history often meant stewardship of vineyards as well. This alliance would persist, reaching a zenith in the medieval wine exploits of the Cistercian monks and the clerical vintners of Champagne, and even later in the great aristocratic châteaux of Bordeaux. By 1000, the mantle of the “independent critic and historian” might have been worn by a monastic chronicler or an estate scribe, noting which vintage excelled or how a plot changed hands; in their annals we find the nascent critical perspective on wine that modern connoisseurs continue to refine.

The year 1000 did not mark an end so much as a turning point. Under the newly crowned Capetian kings, France was entering a period of relative stability and growth. In the next centuries, French wine would flourish on an international scale – from the clarets shipped in quantity to England, to the “vinum regum” of Burgundy acclaimed in Paris, to the frothy celebratory wines of Champagne for coronations. But those later developments rested on the strong roots planted in the Roman and early medieval period. In a very real sense, the grand crus of France were born not in the 1850s or even the 1600s, but in antiquity and the early church. When we consider a glass of French wine today – its complexity, its heritage of place and craft – we are savoring the end result of a story that began in muddy Celtic villages trading for Etruscan amphorae, and continued through Roman villas, barbarian halls, and monastic cellars. By 1000 CE, that story had already spanned fifteen centuries of continuity amid change. It had weathered the fall of an empire and the rise of a faith. It left France with a legacy unlike any other: a culture in which wine was not merely an agricultural product but a cornerstone of civilization. The foundations of French wine were thus secure at the millennium’s dawn – ready to enter a golden age of medieval growth, and eventually to achieve the critical heights we recognize in French wine culture today.