Alsace at the Crossroads: Terroir, Tradition, and Change

From Roman vines to Grand Cru Pinot Noir, Alsace’s dual French-German soul evolves—its DNA intact, its wines’ “personality” shifting.

Alsace is unlike any other French wine region. Nestled in the country’s northeast on the border with Germany, it has long been shaped by both French and German influences—politically, culturally, and viticulturally. This borderland provenance has imbued Alsace with a dual identity: winemaking traditions anchored in centuries of French and Germanic heritage.

The region is famed for producing some of the world’s most age-worthy white wines, often labeled by grape variety (a practice more common in Germany than in France) and bottled in tall flûte bottles. For much of the modern era, Alsace’s wines have been celebrated for their purity, aromatic intensity, and ability to transmit diverse vineyard characters. Yet beneath this continuity, Alsace has never stopped evolving. Over the last decades, subtle but significant shifts—in climate, viticulture, and regulatory framework—have been re-shaping the region’s wine landscape.

The task of the connoisseur is to discern what has changed, and equally what remains enduringly the same. As veteran winemaker Olivier Humbrecht MW observes, Alsace’s “wine identity, its DNA, remains intact; what’s changing is the personality” of its wines. In this long-form analysis, we examine the region’s historical foundations, its unique terroirs and grape varieties, the structure of its appellations, and the recent developments that are quietly redefining Alsace’s place in the wine world.

History and Heritage at the Crossroads

Viticulture in Alsace dates back to antiquity—the Romans cultivated vines here—and by the Middle Ages the region’s wines were renowned across Europe. The 16th century was a golden age for Alsatian wine, when production and quality soared under favorable trade conditions and enlightened local rule. The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) and other conflicts devastated the vineyards—a “30-year war in the 1600s ravaged the villages and vineyards,” as one historical summary notes. In the centuries that followed, Alsace’s fortunes reflected its geopolitical peril.

After 1871, Alsace was annexed by the German Empire, abruptly cutting off its French markets and forcing growers to adapt to new German regulations and tastes. Many vintners banded together in cooperatives—the Ribeauvillé co-op founded in 1895 was one of the first in France (though Alsace was not French at the time). Phylloxera’s arrival late in the 19th century compounded the hardships. Alsace returned to France after World War I, only to be occupied by Germany again during World War II. It finally rejoined France for good in 1945, but its wine industry faced a long recovery.

Unlike Bordeaux or Burgundy, Alsace did not fully integrate into France’s Appellation Contrôlée system until the 1960s. An “Alsace” AOC was approved in 1962, a relatively late date reflecting the region’s post-war reorganization. Even then, the region charted its own course. For example, varietal labeling—virtually unique in French AOCs—remained standard in Alsace, a nod to local tradition and Germanic precedent.

Throughout the 1950s–60s, vignerons replanted vineyards with the so-called noble grapes (Riesling, Gewurztraminer, Pinot Gris, and Muscat) and improved quality, moving away from the high-volume, lesser varieties that had filled cellars after the wars. A defining moment came in 1972 when 4,000 growers staged a protest in Colmar to demand all Alsace AOC wine be estate-bottled rather than sold in bulk. This successful campaign led to a French law in July 1972 requiring bottling at source for Alsace AOC wines. It was a pivotal quality initiative: by eliminating tankers of Alsace wine shipped anonymously to négociants, producers protected the aromatic integrity of their wines and reinforced the region’s identity.

In 1975, Alsace took a further qualitative step by delineating its first Grand Cru vineyard (Schlossberg) to recognize exceptional terroir. Over the next few decades a total of 51 vineyards gained Grand Cru status, formally acknowledged as individual appellations by 2011. The introduction of Alsace Grand Cru AOC wines in the 1980s was not without controversy. Some top producers felt the initial Grand Cru rules were too generous in geographic extent or too rigid in varietal restrictions, and a few famously refused to use the designation.

Maison Trimbach, for example, long withheld the Grand Cru label from its Riesling Clos Ste. Hune even though that vineyard lies within the Rosacker Grand Cru—relying instead on its own reputation to signal quality. (Such was the Trimbachs’ confidence in the Clos’ singular identity that they marketed it simply as Ribeauvillé Riesling for decades.) These debates eventually led to stricter delineation of Grand Cru boundaries and yields, but they also underscored an important aspect of Alsace: tradition and reputation often carry as much weight as official classifications in the region’s conservative wine culture.

Amid these structural changes, Alsace also codified its late-harvest traditions. In 1984 the terms Vendange Tardive (late harvest) and Sélection de Grains Nobles (botrytis-select harvest) were given precise legal definition in Alsace. These designations, used exclusively for the noble grapes, formalized what forward-thinking domaines like Hugel had pioneered: the production of rich, sweet wines from exceptionally ripe or botrytized grapes, in the manner of German Auslese and Beerenauslese. By protecting these terms, Alsace ensured that its centuries-old practice of crafting opulent late-harvest whites—once a cornerstone of its fame—would be preserved at the highest standard of integrity.

Alsace’s 20th-century renaissance thus rested on twin pillars: rigorous appellation control (to elevate quality and terroir expression), and fidelity to tradition (in grape selection and wine styles). Heading into the 21st century, the region enjoyed a reputation for aromatic, full-bodied whites that could range from dry and steely to luxuriantly sweet—sometimes to the confusion of consumers, since most labels did not indicate sweetness. By the early 2000s, criticism mounted that too many Alsace wines, especially Gewurztraminer and Pinot Gris, had become off-dry or sweet without clear labeling. In response, many producers began voluntarily adjusting styles and communication: Riesling in particular saw a general shift back toward dryness, and some estates adopted sweetness indication scales on back labels. Market preference was clearly swinging toward drier profile wines, even for traditionally rich varieties, and Alsace’s winemakers took note.

Crucially, climate change has accelerated this stylistic evolution. Average temperatures in Alsace have risen, making it easier to ripen grapes to high sugar levels. Riesling and Sylvaner that once struggled for full maturity now achieve it reliably, encouraging dry fermentations. At the same time, the warming climate has greatly improved the prospects for Alsace’s only red grape, Pinot Noir, which in cooler decades often produced thin, pale wines. In short, Alsace enters the mid-2020s in a state of gentle transition: adapting to new environmental realities and market tastes, while striving to maintain the long-term virtues—structure, acidity, ageworthiness—that define its legacy.

Geography, Climate and Terroir Diversity

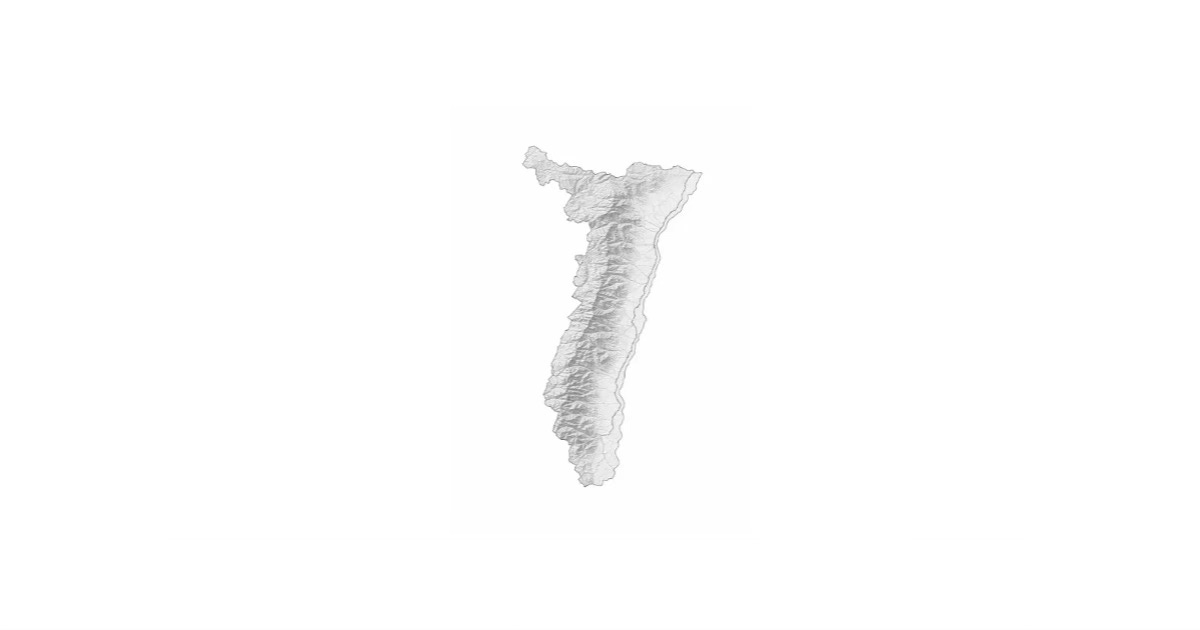

A glance at the map explains much about Alsace’s wine style. The region is a narrow strip (~170 km north to south) running along the east flank of the Vosges Mountains, which separate Alsace from the rest of France. These mountains cast a pronounced rain shadow over the vineyards. Colmar, in central Alsace, receives barely 600 mm of rain per year, making it one of the driest cities in France. This dry, sunny mesoclimate is ideal for grape maturation, allowing an exceptionally long growing season well into late autumn for late-harvest wines.

The summers are warm, but nights remain cool, preserving acidity—a key to Alsace wines’ freshness. The climate is often described as semi-continental: hot in summer, cold in winter, with wide diurnal temperature swings in the ripening season. Crucially, because the Vosges shield against Atlantic weather, Alsace enjoys more sunshine and less rain than most French regions, giving growers great control over ripening and harvest timing.

Most Alsace vineyards lie on the lower slopes and foothills of the Vosges, at elevations roughly 200–400 meters, facing east or southeast toward the Rhine plain. Here lies another of Alsace’s treasures: a mosaic of at least 13 distinct soil types spread across a jumbled geology. Over geologic time the rifting of the Rhine graben and uplifting of the Vosges created a patchwork of rock outcrops and alluvial fans. As a result, within a few kilometers one can find granite, gneiss, schist, volcanic porphyry, sandstone, limestone, marl, clay, loess and more. Each soil imparts its nuance to the wines.

For example, granite and gneiss yield racy, aromatic wines; limestone beds (as at the famous Rosacker and Schlossberg vineyards) give tightly wound, long-aging wines with pronounced acidity; sandstone can produce elegantly fruity, “lively” expressions; clay-marl soils favour fuller-bodied, spicy wines, and volcanic soil (as at Rangen) imparts smokiness and mineral depth. These are classic generalizations—in reality many Grand Cru sites feature complex soil intermixing—but they underscore a crucial point: Alsace is one of the most geologically diverse wine regions on earth, and this diversity underpins the profusion of terroir-driven bottlings from specific sites.

The region’s topography further influences mesoclimates. Vineyards tucked into valley cuttings or on higher slopes may see cooler temperatures or longer morning shadows, delaying ripening slightly compared to those on open mid-slopes. Proximity to the Rhine River (which flows along Alsace’s eastern edge) also moderates temperature in the lowest sites, although the finest vineyards tend to be on the upper benchland for better sun exposure and drainage.

In the north (Bas-Rhin department), the climate is marginally cooler and wetter than in the south (Haut-Rhin), and historically the grandest wines hailed mostly from the latter. Indeed, the Haut-Rhin contains the majority of the Grand Cru vineyards and the most venerated domaines, especially around the towns of Riquewihr, Hunawihr, Ribeauvillé, Turckheim, Colmar, and Thann. The Bas-Rhin, closer to Strasbourg, has fewer grand cru sites (and those were recognized later), but it too possesses distinguished terroirs now coming into their own as vignerons invest in them.

In sum, Alsace’s terroir is a tapestry of myriad small pieces. This is a region where one village’s Riesling might taste markedly different from the next’s, purely by virtue of soil and site. From the windswept granite of Schlossberg to the fossil-rich calcareous soil of Clos Sainte Hune, from the volcanic ash of Rangen to the gypsum-laced marl of Zotzenberg, Alsace offers a spectrum of terroir expression unmatched in French white wine. This helps explain why Alsace has embraced the notion of named vineyards and crus more akin to Burgundy than to its neighboring regions. If terroir is defined as the imprint of place on wine, Alsace is an ideal case study—and over the decades, its appellation system has steadily evolved to bring each terroir’s identity into sharper focus.

Grapes, Wine Styles, and the “Couleurs” of Alsace

Alsace is justly celebrated as a white wine region. Fully 90% of Alsace’s output is white wine, an overwhelming proportion even in a country famous for Chardonnay and Chenin. The climate and soils of Alsace are especially suited to aromatic white grape varieties, and the region’s traditions have long favored them. Chief among these are the four noble grapes of Alsace: Riesling, Gewurztraminer, Pinot Gris, and Muscat. These varieties (plus the less-aromatic Sylvaner in one historical vineyard) are the only ones permitted in Grand Cru wines, and they form the core of Alsace’s identity.

Riesling: The King, Now Firmly Dry

Riesling is often called the king of Alsace. In contrast to German Rieslings, Alsace Riesling is traditionally fermented dry (especially in recent vintages) and yields a full-bodied, firmly structured wine with high acidity and profound aging potential. The best examples—from Grand Cru sites like Schlossberg, Brand, or Saering, or from iconic clos vineyards—can age for decades, developing bouquet and complexity while retaining a backbone of bright acidity and minerality.

Riesling is the most planted Alsace variety today (about 22% of vineyard area in recent surveys), and it is the flagship of many leading domaines. Its style ranges from taut citrus-and-steel in cooler, stonier sites to more ample, peachy profiles in richer limestone or clay soils, but always with a honed balance. Dry Riesling is the standard-bearer of Alsatian viticulture, often used to demonstrate a vineyard’s character with clarity.

Gewurztraminer: The Flamboyant Emblem

Gewurztraminer is Alsace’s most flamboyant grape. It yields intensely aromatic wines—redolent of lychee, rose petal, spices—with a natural richness and oily texture. Gewurztraminer ripens to high sugars with ease, and traditionally many Gewurz wines were made off-dry or semi-sweet to balance their formidable weight and alcohol. Indeed, Gewurztraminer reaches some of the highest natural alcohol levels of any classic grape (14% and above not uncommon).

In the 1990s-2000s this led to criticisms of heaviness; today there is a slight trend to pick Gewurz earlier or ferment it drier for better freshness. Nonetheless, Gewurztraminer remains an Alsatian emblem, especially for late-harvest wines. Its affinity for noble rot makes it a top candidate for Vendange Tardive and SGN bottlings, which can be spectacularly rich and sweet—honeyed, tropical and lush—yet supported by ample acidity and phenolic structure.

Gewurztraminer constitutes roughly 18% of vineyard area, and some of the most coveted sites (e.g. Grand Cru Hengst, or Sporen in Riquewihr) are particularly suited to it, yielding powerful wines that can age surprisingly well.

Pinot Gris: Formerly “Tokay,” Always Serious

Pinot Gris (formerly called Tokay d’Alsace, though unrelated to Hungarian Tokaji) is another cornerstone. Alsatian Pinot Gris is a far cry from the innocuous Pinot Grigio style; here it produces full-bodied, smoky, richly textured whites. In youth Pinot Gris can show notes of pear, almond, smoke, and mushroom alongside stone fruits. It has slightly lower acidity than Riesling but often a rounder, glycerol mouthfeel.

Pinot Gris in Alsace walks a fascinating line between dry and off-dry—many examples have a touch of residual sweetness, although the modern trend is toward drier interpretations unless designated late harvest. It excels in terroirs with some clay or volcanic soil that contribute body and spice. Representing about 15% of plantings, Pinot Gris has gained in prominence over the last 30 years, overtaking Sylvaner in acreage. It is also used, in its fresher incarnation, as a component of Crémant d’Alsace (sparkling) blends.

Muscat: Dry, Grapey, Historically Esteemed

Muscat in Alsace usually refers to Muscat Blanc à Petits Grains and Muscat Ottonel, often blended. True Alsace Muscat is vinified dry and is prized for its grapey, floral aromatics. It can be exquisite as a young, dry aperitif wine, though it’s less favoured for long aging. Only about 2% of vineyards are Muscat—it is a niche but historically esteemed variety, completing the quartet of noble grapes. In certain grand crus (such as Kirchberg de Barr or Altenberg de Bergheim) Muscat achieves memorable expression, but it is sensitive to weather and more irregular to grow.

Beyond the “Noble Four”: Pinot Blanc, Auxerrois, Sylvaner, Chasselas

Beyond the noble four, Alsace cultivates several other grapes that play important roles in everyday wines. Pinot Blanc is common, often used for the lighter entry-level whites and for Crémant. The name Pinot Blanc on an Alsace label can be a bit misleading, as these wines often include a proportion of the similar Auxerrois Blanc grape—which is not separately indicated. Such blends yield soft, fruity dry whites ideal for casual drinking.

Sylvaner, once the dominant grape of Alsace in the 19th century, survives today in a much reduced but qualitatively improving role (about 8–9% of plantings). Good Sylvaner, from old vines in fertile yet well-drained soils, gives a brisk, herbaceous wine with surprising cut and salinity—and in one Grand Cru, Zotzenberg, Sylvaner even holds elite status by historical exception. Chasselas (locally called Gutedel) was traditionally a mass-production grape and is now very scarce (under 1% of vines).

Pinot Noir: From Pale Curiosity to Grand Cru Reality

Pinot Noir stands apart as Alsace’s sole red grape. It covers roughly 10–11% of vineyard area and is rapidly gaining attention. In the past, Alsace Pinot Noir was typically light, fresh and best consumed young—a rosé or very pale red style often compared to a light-bodied Burgundy or a Beaujolais. Grown in cooler sites and made without oak, it was charming but rarely profound.

However, warmer growing seasons and improved viticulture have given new impetus to Pinot Noir in Alsace, enabling fuller ripeness and more structured wines. Many producers now craft two levels of Pinot: a lighter, fruit-forward style (sometimes explicitly labeled Pinot Noir d’Alsace Rouge Léger, meant to be served slightly chilled) and a more serious barrel-aged cuvée from better parcels. The latter can display impressive depth of cherry fruit, earthy minerality from calcareous soils, and fine tannins—in blind tastings, top Alsace Pinot Noirs can approach good Côte d’Or Burgundies in quality.

Recognizing this progress, regulators have in recent years elevated Pinot Noir’s status. Starting with the 2022 vintage, two grand cru vineyards—Kirchberg de Barr and Hengst—have been authorized to produce Grand Cru Pinot Noir (the first time red wine has ever been allowed the grand cru label in Alsace). And in 2024 a third site, Vorbourg, was approved, bringing Pinot Noir officially into the highest echelon of Alsatian terroirs. These developments mark a historic broadening of Alsace’s wine spectrum. No longer “a rather thin and notably light wine,” Alsace Pinot Noir is “growing into serious Pinot” worthy of cru status, as one observer noted.

The “Colours” of Alsace: White, Red, Rosé, Orange—And Sparkling

In terms of wine “colours,” Alsace is predominantly white, but it produces reds and rosés as well. The reds, as discussed, are Pinot Noir in still form. Rosé in Alsace is almost exclusively found as Crémant d’Alsace Rosé, the traditional-method sparkling wine made typically from 100% Pinot Noir (pressed gently to a pale pink hue). A tiny amount of still rosé exists, usually as a byproduct of short maceration Pinot Noir; it remains a curiosity rather than a staple.

Orange or skin-contact wines are not traditional in Alsace, but a few innovative winemakers have begun experimenting with them (for example, extended skin maceration on Gewurztraminer or Pinot Gris, yielding amber-hued, tannic whites). These “orange” wines are outside AOC norms but demonstrate the experimental undercurrent in the region as younger vignerons explore natural and ancestral methods. Still, such wines are a small fringe. The classic Alsace palette continues to be dry whites, sweet late-harvest whites, sparkling whites/rosés, and a modest but growing proportion of reds.

Vendange Tardive and Sélection de Grains Nobles: Defined in 1984, Revered for Decades

No discussion of Alsace styles would be complete without emphasizing the late-harvest specialities and sweet wines. When conditions allow (i.e. a long autumn with some botrytis development), producers may designate a wine Vendange Tardive (VT) if the grapes achieved a high natural sugar level at harvest, or Sélection de Grains Nobles (SGN) for an even richer wine made from individually picked noble-rotted grapes. These wines, made only from the noble varieties, are lusciously sweet and tremendously aromatic—yet thanks to Alsace’s climate, they also possess formidable acidity that prevents them from being cloying.

An SGN Riesling or SGN Gewurztraminer from a top estate is one of the great dessert wines of France, capable of aging 50+ years, on par with fine Sauternes or Trockenbeerenauslese. VT wines are a step down in intensity—often more semi-sweet or sweetish rather than fully dessert-like—and can sometimes be enjoyed with savory courses (foie gras with VT Gewurztraminer is a classic regional pairing). Both VT and SGN were officially defined in 1984 with strict minimum sugar levels and tasting-panel approvals, ensuring that the terms signify exceptional products.

It is a testament to Alsace’s climate (dry autumns) that such styles can be made almost every other year in one grape or another. However, with climate warming, harvest times have shifted earlier, and botrytis is becoming slightly less frequent; producers thus treat VT/SGN wines as precious heralds of special vintages. Meanwhile, demand for sweet wines globally has declined in recent years, and many Alsace domains have scaled back these offerings or focused on making them more balanced. Increasingly, the sweet wines are seen less as objects of opulence and more as part of the region’s patrimony to be maintained in limited quantity.

Crémant d’Alsace: Authorized in 1976, Now a Powerhouse

Finally, we must highlight Crémant d’Alsace, the region’s sparkling wine. First authorized in 1976, Crémant d’Alsace has become remarkably successful—it is today the leading French sparkling AOC after Champagne, both in volume and reputation. Made by the traditional method (secondary fermentation in bottle) from allowed grapes (commonly Pinot Blanc, Auxerrois, Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Riesling, and Pinot Noir for rosé), Crémant d’Alsace tends to be fresh, floral, and elegant, usually without heavy autolytic flavors (as the wines are released relatively young). Styles range from brut nature to demi-sec, though brut is most typical.

Over 40 million bottles of Crémant d’Alsace are produced annually, representing roughly one quarter to one-third of Alsace’s total wine output. This figure has grown as producers leverage Crémant’s commercial appeal; sparkling production has proven a boon for utilizing grapes from cooler sites or abundant years. Crémant’s rise illustrates how Alsace is not just a still-wine region but also a sparkling wine powerhouse, offering an alternative to Champagne that, at its best, marries Alsatian aromatic precision with celebratory finesse.

Notably, Crémant also provides an outlet for Chardonnay, a grape not permitted in Alsace still AOC wines but allowed in sparkling blends. Most Crémant d’Alsace is NV (non-vintage) and meant for early drinking. However, a few ambitious producers age their Crémants on lees for extended periods or millésime (vintage-date) their bottlings, showcasing that even within this category, terroir and house styles play a role. With over a third of all Alsace bottles now being Crémant, sparkling wine has become an integral “colour” of Alsace’s spectrum—one more facet of its evolving identity.

Appellations and Classification System

The Alsace wine appellation structure is unique in France, mirroring the region’s blend of innovation and tradition. There are three primary AOC designations: Alsace AOC (sometimes labeled Vin d’Alsace), Alsace Grand Cru AOC, and Crémant d’Alsace AOC. Within these broad categories, however, lies a complex hierarchy of geographic indications introduced over time to highlight the region’s myriad terroirs.

AOC Alsace (1962): Varietal Purity, Regional Breadth

AOC Alsace (est. 1962) is the base appellation covering the entire region for still wines. Nearly 70–75% of Alsace’s production falls under this regional AOC, which permits all main grape varieties. In practice, an “Alsace AOC” wine is often varietally labeled (e.g. “Alsace Riesling” or “Alsace Pinot Noir”), and by law it must contain 100% of the named grape.

There are eight permitted varietals for Alsace AOC: the noble four (Riesling, Gewurztraminer, Pinot Gris, Muscat) plus Pinot Noir, Pinot Blanc (Auxerrois), Sylvaner, and Chasselas. If a wine is a blend, it cannot list multiple grapes on the front label; traditionally such blends were called Edelzwicker (a simple field blend) or more recently Gentil (a superior blend with at least 50% noble grapes). However, since blends do not fit the monovarietal labeling norm, most quality-focused producers bottle their blends under proprietary names or, if from a single site, under that lieu-dit name (see below).

2011: Commune and Lieu-dit Indications

Within the Alsace AOC category, a significant reform in 2011 allowed the introduction of two sub-category indicationsto bridge the gap between generic Alsace and Grand Cru. These are: Commune appellations and Lieu-dit (single-vineyard) appellations.

Thirteen communal designations were defined, corresponding to certain villages or sectors with historically recognized quality. These names—including Bergheim, Blienschwiller, Côtes de Barr, Côte de Rouffach, Coteaux du Haut-Koenigsbourg, Klevener de Heiligenstein, Ottrott, Rodern, Saint-Hippolyte, Scherwiller, Vallée Noble, Val Saint-Grégoire, and Wolxheim—may now be indicated on labels alongside “Alsace” to denote the wine’s geographic origin and typicity.

Each communal appellation comes with slightly stricter production standards (e.g. lower yield limits) and often an association with particular grapes: for instance, Rouge d’Ottrott and Rouge de Saint-Hippolyte are noted for Pinot Noir, Klevener de Heiligenstein is reserved for the local Savagnin Rose varietal, Scherwiller is associated with Riesling, etc. These village wines function much like “village appellations” in Burgundy—a step up from generic regional wine, intended to showcase a classic style of that locale.

Similarly, the Lieu-dit designation allows around 200–300 specific vineyards or localities outside of the Grand Cru system to be named on the label (with official recognition) if the wine meets enhanced requirements. Many of these sites were unofficially celebrated for years by domaines that printed the vineyard name on their labels; since 2011, they have a formal framework. A Lieu-dit Alsace wine must typically come from a single named vineyard, adhere to higher ripeness and lower yield standards than basic AOC, and is meant to express the terroir imprint of that site. This movement reflects a generation of vignerons dedicated to defending terroir-driven wines even at the “village cru” level.

Alsace Grand Cru AOC: 51 Vineyards, 55 hl/ha, ~3–4% of Output

Above this lies Alsace Grand Cru AOC, representing the pinnacle of terroir classification. Between 1975 and 1992, Alsace identified 51 vineyards as Grand Crus, each now an individual AOC in its own right (since 2011) with its name appended (e.g. Alsace Grand Cru Rangen de Thann). These sites range from just over 3 hectares to more than 80 hectares in size, and they span a variety of soil types and elevations. What they share are exceptional mesoclimates and historical reputations for producing superior wines.

Grand Cru rules originally restricted grape varieties to the noble four (Riesling, Gewurz, Pinot Gris, Muscat), with one special case: Sylvaner was allowed in Zotzenberg due to tradition. (Recent amendments have also permitted a few blends or other exceptions in certain Grand Crus, recognizing, for example, that some terroirs were historically planted to multiple grapes.) Grand Cru wines must meet the strictest criteria: yields are capped at 55 hl/ha—considerably lower than the 80 hl/ha general limit for Alsace AOC—and grapes must reach higher minimum ripeness. The wines are intended for maturation; many Grand Crus are released later or benefit from extra bottle age before sale.

In practice, Grand Cru designation has greatly elevated Alsace’s profile in fine wine circles, although it also introduced complexities. Because the vineyards differ widely in character (a volcanic Grand Cru in the south will produce a very different wine from a limestone Grand Cru in the north, even with the same grape), mastering the vocabulary of 51 crus is a connoisseur’s endeavor. Some critics argued that certain included sites were less deserving, while omitted ones perhaps should qualify—debates common to any classification.

Nevertheless, the Grand Cru system is now firmly entrenched and generally accepted by the region (nearly all top estates, including holdouts, now use Grand Cru labeling for applicable wines, with a few individualistic exceptions). Grand Cru wines still account for only ~3–4% of Alsace’s total output, but they represent the most ambitious expressions of its terroirs.

2022 and 2024: Grand Cru Pinot Noir Arrives

One of the most significant recent changes in the Grand Cru sphere was the aforementioned approval of Pinot Noir for certain Grands Crus. Historically, only white wines could be Grand Cru in Alsace (the logic being that the noblest vineyards were planted to noble white varieties). But with Pinot Noir’s rise in quality, local institutions pushed for its recognition.

After years of lobbying and audits, in 2022 the INAO (France’s appellation authority) agreed to allow red wines from Kirchberg de Barr and Hengst Grands Crus to be labeled as Grand Cru—a landmark decision ending an exclusivity dating back to 1975. As noted, Vorbourg Grand Cru has since joined this select group, meaning three grands crus (so far) can produce red Grand Cru Alsace. Those Pinot Noir grapes must meet Grand Cru standards (including a minimum planting density and ripeness, and aging in oak is common for these wines) to carry the prestigious label. This change reflects not only climate warming enabling better reds, but also a cultural broadening of what constitutes greatness in Alsace wine. It’s a measured evolution—essentially grafting a red branch onto a white vine of tradition.

An Emerging Middle Tier: Premier Cru

At the other end of the hierarchy, an initiative is underway to further refine classifications with an intermediate tier: Alsace Premier Cru. Recognizing that the gap between basic Alsace and lofty Grand Cru is wide, and that many excellent vineyard sites exist just below Grand Cru status, producers have proposed a Premier Cru category analogous to Burgundy’s.

As of the mid-2020s this plan is still in development, but momentum is building. In fact, in December 2016 the INAO began reviewing a Premier Cru dossier, and there have been “whispers” of which lieux-dits might be promoted when the scheme materializes. The Association of Alsace Young Winemakers even created an official map of recognized lieux-dits in 2020 as a preparatory step.

The Premier Cru campaign is driven by economic and qualitative logic—to give consumers a clearer middle category and to reward terroirs that consistently produce superior wines but are not (or not yet) classified as grand cru. If approved, Alsace Premier Cru would likely encompass on the order of 100 or more sites. This impending development signifies the continued maturation of Alsace’s appellation system, bringing it closer to parity with Burgundy’s nuanced hierarchy, while affirming that a wine region with such complex geology benefits from more finely grained distinctions.

Crémant d’Alsace AOC: 12 Months Lees, Hand Harvest, 80 hl/ha

Finally, Crémant d’Alsace AOC is the separate appellation for Alsace sparkling wines made by the traditional method. Established in 1976, its rules are in line with other Crémant regions: only authorized grape varieties, second fermentation in bottle, minimum 12 months aging on lees, mandatory hand-harvesting, and a yield limit (80 hl/ha) slightly higher than for still wine. A noteworthy allowance is that Chardonnay is permitted in Crémant (even though not in still Alsace AOC), reflecting the practical need for suitable base-wine grapes.

Crémant d’Alsace has thrived under these regulations, to the point that over 108 million bottles of Crémant are produced in France annually, and roughly 40% of those—about 40 million—come from Alsace. The appellation’s success underscores Alsace’s adaptability: here is a region known for still whites managing to excel in fizz by leveraging its cool climate grapes and technical acumen.

In summary, Alsace’s appellation framework is both traditional and dynamic. It respects longstanding notions (like the primacy of certain grapes and sites) yet has proven flexible—evolving to include villages, lieu-dits, a possible Premier Cru tier, and even expanding the definition of Grand Cru over time. This reflects the region’s pragmatism: the goal is always to balance the preservation of terroir character with the need to sustain Alsace’s relevance in a changing wine market. Every appellation tweak or new classification is effectively an attempt to fine-tune that balance.

Vignerons, Viticulture and the Contemporary Scene

Alsace’s vineyards may be ancient, but its vineyard ownership and viticultural practices continue to adapt. The region today has around 3,500 winegrowers and about 15,500 hectares under vine—an average holding of only a few hectares per grower, indicating how fragmented the landscape is. However, not all growers bottle their own wine. A significant portion of the production is handled by cooperatives and négociant houses.

Cooperatives have deep roots here: faced with adversity in the late 19th century, Alsace winegrowers were early pioneers of the co-op model (the Cave de Ribeauvillé founded in 1895 is often cited as France’s first wine co-op). Today, 15 cooperatives produce around 40–45% of Alsace’s wine. The largest, such as Bestheim and Wolfberger, each vinify grapes from well over 1,000 hectares and account for a substantial share of total output.

Unusually, Alsace’s co-ops are known for maintaining quality—an expert assessment in 2017 opined that no French region has a “more consistent or attractive co-operative wine offer” than Alsace. This is attributed to healthy competition among co-ops and the fact that even co-op wines must compete in the marketplace on varietal character and terroir, thus incentivizing quality. The cooperatives have been instrumental in sustaining small family vineyards (some growers deliver to co-ops across multiple generations) and in broadening distribution for Alsace wines domestically and abroad.

Alongside the co-ops stand numerous family-owned domaines, including names of considerable renown. Many of these families have tended vines for centuries—the Hugels, Trimbachs, Beyers, and others date to the 17th–18th century or earlier—and became standard-bearers for Alsace after World War II by bottling under their own names. Domaine Zind-Humbrecht, for example, now in the 13th generation of the Humbrecht family, helped drive an ethos of terroir-focused, low-yield, organically farmed wines since the 1990s. The Faller family of Domaine Weinbach (established 1898 in Kaysersberg’s old Capuchin monastery) likewise built a legacy on exquisite Rieslings and Gewurztraminers that expressed individual vineyard plots.

Famous négociant-producers like Maison Trimbach (founded 1626) and Maison Hugel (founded 1639) have remained family-managed while achieving global recognition, largely through consistently excellent signature wines (Trimbach’s Clos Ste. Hune Riesling and Cuvée Frédéric Émile, Hugel’s Vendange Tardive and SGN Sélections) that embody the region’s highest standards. These houses proved that Alsace wine could attain world-class stature and longevity, bolstering the region’s credibility in fine wine markets. Crucially, even the larger négociants in Alsace (unlike in some regions) tend to be family-run and quality-oriented; mass industrial players are absent, which has helped maintain a culture of pride and accountability in production.

Viticulturally, Alsace has seen a quiet revolution in the past 20–30 years. The dry climate, which reduces disease pressure, and a philosophical alignment with nature have made Alsace a leader in organic and biodynamic viticulture. As of mid-2020s, over 36% of Alsace’s vineyard area is certified organic and more than 8% biodynamic—among the highest proportions of any major wine region in the world. Pioneers like François Barmès, Olivier Humbrecht MW, and Gérard Schueller were early adopters of biodynamics in the 1990s, and now a new generation (e.g. Jeunes Vignerons d’Alsace association) carries that torch, mapping lieux-dits and focusing on sustainable practices.

The prevalence of organic viticulture means fewer chemical inputs, more cover-cropping and biodiversity, and an emphasis on hand harvesting (already mandatory for Grand Cru and Crémant production). In the best cases, this has translated into wines of greater purity and site-expression, with producers claiming deeper root health and soil microbiome activity as factors in quality. With over one-third of growers “farming without chemicals”, Alsace has effectively returned to its pre-industrial farming ethos, albeit with modern knowledge to combat vineyard threats organically.

At the same time, there’s been an evolution in oenological style. Traditionally, Alsace wines were fermented in large old oak casks (often ornately carved foudres) and left on the fine lees for an extended period, but without bâtonnage or new oak influence—yielding clean, varietally pure wines. That practice largely remains, as most producers eschew strong oak flavors in Alsace whites (the delicate aromatics would be overwhelmed).

However, some changes have occurred: many winemakers now ferment in stainless steel or fiberglass vats for precise temperature control, especially for aromatic whites, and then may age the wines briefly in neutral casks or tanks. A trend toward longer lees contact (sometimes sur lie aging well beyond fermentation) has emerged to enrich textures, particularly for Riesling and Pinot Gris. Conversely, a few natural-leaning winemakers experiment with skin contact or amphora aging for certain cuvées, expanding the stylistic diversity.

Overall, technical control in wineries is high—the region has first-rate enological facilities, and even the co-ops have modern presses and labs. This ensures a baseline of sound winemaking, which, combined with low yields at top estates (some Grand Cru plots are cropped at far below the legal maximum), results in consistently high quality. One could argue that variation in Alsace wines today has more to do with site and winemaker philosophy than with flaws or failures; the era of unclean, oxidative wines is largely past.

In terms of quantity vs. quality, Alsace has at times had to navigate the peril of overproduction. The push to reclaim vineyard land after WWII saw extensive plantings, including on the fertile plain. Wines from these high-yield sites could be dilute, threatening the region’s reputation in the 1980s when supply outstripped demand. The Grand Cru system and the modern focus on delineating superior sites were, in part, a response to this—to clearly identify the sources of the best wines and encourage growers to limit yields. Today, most serious producers impose yield restrictions well below the allowances, and less of the undistinguished bulk wine ever reaches export. The internal structure of the industry, with cooperatives absorbing large volumes for branded wines and large houses maintaining quality control, has actually helped by providing an outlet for the more commercial wines while allowing independent domaines to concentrate on distinctive bottlings.

One symbolic update in recent years encapsulates Alsace’s willingness to modernize: the legal requirement that all Alsace AOC wine be bottled in the traditional “Rhine flute” bottle was lifted in 2022. For decades, Alsace insisted on the tall, slender green bottle for its still wines—a marketing identity but also a point of contention for those who found it impractical or outdated. With new rules, producers may choose alternative bottle shapes (a slightly shorter, more Burgundian-style bottle, for instance). While this might seem a trivial detail, it signals a break from strict traditionalism in favor of producer autonomy and perhaps a hint of rebranding. Some estates immediately adopted new bottles for certain wines, whereas others stick with the flute, proving again that in Alsace tradition and change coexist delicately.

Recent Developments and Long-Term Outlook

As Alsace moves further into the 21st century, it faces a confluence of challenges and opportunities that will shape its future trajectory. Key among these is climate change, which has already made its mark. The region is experiencing warmer growing seasons on average, leading to higher potential alcohol levels in grapes and occasionally lower acidities. This has mandated adjustments in both vineyard and cellar: picking dates have crept earlier to preserve acids; canopy management is tweaked to protect grape bunches from sun; and winemakers are experimenting with partial malolactic fermentations or longer lees aging to balance the resulting wines.

On the positive side, certain varieties are benefiting—Pinot Noir, as discussed, now achieves phenolic ripeness more consistently, enabling deeper-colored and more complex reds that were rare a generation ago. Some growers have even mused about introducing other red varieties in the far future (the tongue-in-cheek suggestion of Syrah d’Alsace has been floated in wine circles). While Alsace’s cool nights and northerly latitude still make it a white wine haven, the climate trend is undeniable.

Fortunately, the region’s natural acidity and dry climate give it resilience—unlike areas that struggle with rain or rot under warmth, Alsace manages to ripen earlier without catastrophic disease, so the main issue is balance rather than viability. In the long term, expect to see more emphasis on site selection for appropriate varieties (e.g. planting Riesling and Pinot Noir in cooler higher elevations, reserving the warmest sites for late-ripeners like Gewurztraminer or for reds). The newly allowed Grand Cru Pinots may be just the beginning of a broader adaptation to climate.

Another development is in the realm of wine style and consumer alignment. After years of critique for hidden sweetness in ostensibly dry wines, many producers have coalesced around making their flagship Rieslings bone-dry (often under 5 g/L residual sugar) unless specifically a VT or SGN. There is also talk of instituting an official sweetness scale on labels; while not yet mandatory, some propose an index similar to Germany’s (ranging from dry to sweet) to guide buyers. The regional wine body, CIVA, has debated this, recognizing that clarity could enhance Alsace’s reputation for serious gastronomy-friendly wines. So far, changes have been voluntary: for example, Domaines Schlumberger and Zind-Humbrecht have used back-label sweetness meters. The trend toward drier, more gastronomic wines dovetails with global tastes and should serve Alsace well in fine dining contexts, where its wines already shine with cuisines ranging from classic French to spicy Asian (Riesling and Gewurztraminer being famously versatile).

The economic aspect cannot be ignored. Alsace, while esteemed, has sometimes struggled in the international market—partly due to that confusion over sweetness and grape names unfamiliar to some consumers. However, the emphasis on terroir and classification (Grand Cru, lieu-dit) is gradually rebranding Alsace as a collector’s region akin to Burgundy or the Rhône. Wine critics and sommeliers increasingly highlight the top vineyard sites and domaines, bringing renewed prestige.

At the same time, the value proposition of Alsace wines is extraordinarily high: even the very best Grand Cru Rieslings often cost a fraction of equivalent Burgundies or German Grosses Gewächs. This is a point of potential growth—as connoisseurs seek out great dry white wines beyond the obvious, Alsace stands to gain a larger following. The region’s ability to offer both affordable, approachable wines (like easy-drinking Pinot Blanc, Crémant, etc.) and blue-chip fine wines is a strength few regions share.

Internal to Alsace, the social fabric of winemaking is evolving with the new generation. Young winemakers, many trained abroad or in enology schools, are bringing fresh ideas but also recommitting to the core ethos of terroir-driven quality. They have formed associations (like the Jeunes Vignerons group) to promote organic viticulture and push initiatives like the Premier Cru classification. There is a palpable energy in this cohort to ensure Alsace stays relevant.

We see more collaborative promotions, more tourism initiatives (the Alsace Wine Route, established in 1953, remains one of the most popular wine trails in Europe), and an increased openness to oenotourism and direct-to-consumer sales. While Alsace is traditionally a rather insular region—many wineries historically sold majority of their production in France or nearby Switzerland/Belgium/Germany—there is now greater marketing outreach to Anglophone markets and Asia. Exports are a focus for growth, and highlighting the distinctiveness of Alsace’s culture (the food, the fairy-tale villages, the Christmas markets, etc.) has been part of that strategy, though always with an eye to avoiding crass commercialization of what is, at heart, a very authentic wine culture.

In the vineyard, aside from organics, another subtle change is the varietal makeup. Sylvaner, once dismissed, is seeing a mini-revival (helped by the reputation of old-vine Sylvaner from places like Grand Cru Zotzenberg and Mittelbergheim’s limestone vineyards). Some winemakers champion it as an “underrated, versatile, dry white” that can give refreshing, terroir-transparent wines when yields are controlled. Likewise, a few are experimenting with Piwi (fungus-resistant hybrid) grape varieties in pilot projects, as a nod to sustainable future options, although none are in AOC wines yet. The retention of heritage grapes like Klevener (Savagnin Rose) in Heiligenstein also shows that Alsace values its peculiarities; that communal varietal, while tiny in production, remains codified to preserve diversity.

Perhaps the most heartening aspect of Alsace’s evolution is that, despite change, its core strengths remain structurally intact. The region still produces superb dry Rieslings with “fountain-like freshness and bracing natural acidity”, succulent Gewurztraminers with exotic perfume, and Pinot Gris of generous texture—styles consistent with descriptions from decades past. The packaging and presentation may shift (flutes vs. modern bottles, back-label info, etc.), but the wines inside continue to reflect the vineyard and the year, just as they did in prior generations. As Humbrecht’s quote suggested, the personality is adjusting but the identity endures.

Thus, Alsace’s long-term outlook is one of cautious optimism: a region holding fast to what makes it unique (terroir, tradition, typicity) while making incremental, thoughtful adjustments to thrive in a changing world.

In a sense, Alsace exemplifies the notion of a “living classic”—a wine region with deep historical roots that is very much alive to contemporary dynamics. Its wines carry the imprint of monastic meticulousness, peasant tenacity, and familial pride, yet they are increasingly relevant to modern preferences for authenticity, sustainability, and diversity of style.

For the serious wine lover, Alsace offers both the comfort of the familiar (the rolling vineyards under medieval hilltop castles, the purity of a cold Riesling from granite soil) and the intrigue of the new (a Pinot Noir from a site formerly known only for whites, or an ancient field blend reborn in biodynamic glory). With its blend of French grandeur and German precision, Alsace has quietly persisted, never loudly trumpeting its virtues, yet consistently delivering wines of character and pedigree. As the region continues to adapt—whether through new appellations, vineyard practices, or wine styles—it does so from a position of earned authority. Alsace knows what it is: a singular wine region at the crossroads, blessed by terroir and steered by tradition. The task ahead is simply to let that identity shine through every bottle, for generations to come.